- 《答聶文蔚》 [2017/04]

- 奧巴馬致女友:我每天都和男人做愛 [2023/11]

- 愛國者的喜訊,干吃福利的綠卡族回國希望大增 [2017/01]

- 周五落軌的真的是個華女 [2017/03]

- 現場! 全副武裝的警察突入燕郊 [2017/12]

- 法拉盛的「雞街」剛剛又鬧出人命 [2017/11]

- 大部分人品太差了--- 中國公園裡的「黃昏戀」 [2019/12]

- 亞裔男孩再讓美國瘋狂 [2018/09]

- 年三十工作/小媳婦好嗎 /土撥鼠真屌/美華素質高? [2019/02]

- 看這些入籍美加的中國人在這裡的醜態百出下場可期 [2019/11]

- 黑暗時代的明燈 [2017/01]

- 文革宣傳畫名作選之 「群醜圖」 都畫了誰? [2024/01]

- 當今的美國是不是還從根本上支持中國的民主運動? [2017/10]

- 香港的抗爭再次告訴世人 [2019/06]

- 中國女歡呼日本地震 歐洲老公驚呆上網反思 [2024/01]

- 加入外國籍,你還是不是中國人?談多數華人的愚昧和少數華人的覺醒 [2018/02]

- 周末逛法拉盛,還是坐地鐵? [2017/10]

- 春蠶到死絲方斷, 丹心未酬血已干 [2017/03]

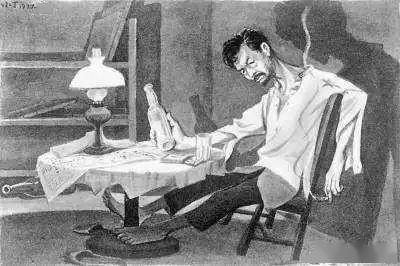

魯迅小說《孤獨者》

寫於:1925 年 10 月 17 日

孤獨者

寫於:1925 年 10 月 17 日

孤獨者

Lu Xun

The Misanthrope

Written: October 17, 1925

The Misanthrope

Written: October 17, 1925

一

我和魏連殳相識一場,回想起來倒也別緻,竟是以送殮始,以送殮終。

My friendship with Wei Lien-shu, now that I come to think of it, was certainly a strange one. It began and ended with a funeral.

我和魏連殳相識一場,回想起來倒也別緻,竟是以送殮始,以送殮終。

My friendship with Wei Lien-shu, now that I come to think of it, was certainly a strange one. It began and ended with a funeral.

那時我在S城,就時時聽到人們提起他的名字,都說他很有些古怪:所學的是動物學,卻到中學堂去做歷史教員;對人總是愛理不理的,卻常喜歡管別人的閑事;常說家庭應該破壞,一領薪水卻一定立即寄給他的祖母,一日也不拖延。此外還有許多零碎的話柄;總之,在S城裡也算是一個給人當作談助的人。有一年的秋天,我在寒石山的一個親戚家裡閑住;他們就姓魏,是連殳的本家。但他們卻更不明白他,彷彿將他當作一個外國人看待,說是「同我們都異樣的」。

When I lived in S——, I often heard him mentioned as an odd fellow: after

studying zoology, he had become a history teacher in a middle school.

He treated others in cavalier fashion, yet liked to concern himself with

their affairs; and while maintaining that the family system should be

abolished, he sent his salary to his grandmother the same day that he

drew it. He had many other strange ways, enough to set tongues wagging

in the town. One autumn I stayed at Hanshihshan with some relatives also

named Wei, who were distantly related to him. However, they understood

him even less, looking on him as if he were a foreigner. "He's not like

us!" they said.

這也不足為奇,中國的興學雖說已經二十年了,寒石山卻連小學也沒有。全山村中,只有連殳是出外遊學的學生,所以從村人看來,他確是一個異類;但也很妒羨,說他掙得許多錢。

This was not strange, for although China had had modern schools for some

twenty years, there was not even a primary school in Hanshihshan. He

was the only one who had left that mountain village to study; hence in

the villagers' eyes he was an undoubted freak. They also envied him,

though, saying he had made much money.

到秋末,山村中痢疾流行了;我也自危,就想回到城中去。那時聽說連殳的祖母就染了病,因為是老年,所以很沉重;山中又沒有一個醫生。所謂他的家屬者,其實就只有一個這祖母,雇一名女工簡單地過活;他幼小失了父母,就由這祖母撫養成人的。聽說她先前也曾經吃過許多苦,現在可是安樂了。但因為他沒有家小,家中究竟非常寂寞,這大概也就是大家所謂異樣之一端罷。

Towards the end of autumn, there was an epidemic of dysentery in the

village, and in alarm I thought of returning to the town. I heard his

grandmother had contracted the disease too, and because of her age her

case was serious. Moreover there was not a single doctor in the village.

Wei had no other relative but this grandmother, who with one

maidservant led a simple life. As he had lost both parents in his

childhood, she had brought him up. She was said to have known much

hardship earlier, but was now leading a comfortable life. Since he had

neither wife nor children, however, his family was very quiet, and this

presumably was one of the things about him considered freakish.

寒石山離城是旱道一百里,水道七十里,專使人叫連殳去,往返至少就得四天。山村僻陋,這些事便算大家都要打聽的大新聞,第二天便轟傳她病勢已經極重,專差也出發了;可是到四更天竟咽了氣,最後的話,是:「為什麼不肯給我會一會連殳的呢?……」

The village was more than thirty miles from the town by land, and more

than twenty miles by water; so that it would take four days to fetch Wei

back. In this out-of-the-way village such matters were considered

momentous news, eagerly canvassed by all. The next day the old woman was

reported to be in a critical state, and the messenger on his way.

However, before dawn she died, her last words being:

"Why won't you let me see my grandson?"

"Why won't you let me see my grandson?"

族長,近房,他的祖母的母家的親丁,閑人,聚集了一屋子,豫計連殳的到來,應該已是入殮的時候了。壽材壽衣早已做成,都無須籌畫;他們的第一大問題是在怎樣對付這「承重孫」〔2〕,因為逆料他關於一切喪葬儀式,是一定要改變新花樣的。聚議之後,大概商定了三大條件,要他必行。一是穿白,二是跪拜,三是請和尚道士做法事〔3〕。總而言之:是全都照舊。

Elders of the clan, close relatives, members of his grandmother's family

and others, crowded the room anticipating Wei's return, which would be

in time for the funeral. The coffin and shroud had long been ready, but

the immediate problem was how to cope with this grandson, for they

expected he would insist on changing the funeral rites. After a

conference, they decided on three terms which he must accept. First, he

must wear deep mourning; secondly, he must kowtow to the coffin; and,

thirdly, he must let Buddhist monks and Taoist priests say mass. In

short, all must be done in the traditional manner.

他們既經議妥,便約定在連殳到家的那一天,一同聚在廳前,排成陣勢,互相策應,并力作一回極嚴厲的談判。村人們都咽著唾沫,新奇地聽候消息;他們知道連殳是「吃洋教」的「新黨」,向來就不講什麼道理,兩面的爭鬥,大約總要開始的,或者還會釀成一種出人意外的奇觀。

This decision once reached, they decided to gather there in full force

when Wei arrived home, to assist each other in this negotiation which

could admit of no compromise. Licking their lips, the villagers eagerly

awaited developments. Wei, as a "modern," "a follower of foreign

creeds," had always proved unreasonable. A struggle would certainly

ensue, which might even result in some novel spectacle.

傳說連殳的到家是下午,一進門,向他祖母的靈前只是彎了一彎腰。族長們便立刻照豫定計畫進行,將他叫到大廳上,先說過一大篇冒頭,然後引入本題,而且大家此唱彼和,七嘴八舌,使他得不到辯駁的機會。但終於話都說完了,沉默充滿了全廳,人們全數悚然地緊看著他的嘴。只見連殳神色也不動,簡單地回答道:

「都可以的。」

「都可以的。」

He arrived home, I heard, in the afternoon, and only bowed to his

grandmother's shrine as he entered. The elders proceeded at once

according to plan. They summoned him to the ball, and after a lengthy

preamble led up to the subject. Then, speaking in unison and at length,

they gave him no chance to argue. At last, however, they dried up, and a

deep silence fell in the hall. All eyes fastened fearfully on his lips.

But without changing countenance, he answered simply:

"All right."

"All right."

這又很出於他們的意外,大家的心的重擔都放下了,但又似乎反加重,覺得太「異樣」,倒很有些可慮似的。打聽新聞的村人們也很失望,口口相傳道,「奇怪!他說『都可以』哩!我們看去罷!」都可以就是照舊,本來是無足觀了,但他們也還要看,黃昏之後,便欣欣然聚滿了一堂前。

This was totally unexpected. A weight had been lifted from their minds,

yet their hearts felt heavier than ever, for this was so "freakish" as

to give rise to anxiety. The villagers looking for news were also

disappointed, and said to each other, "Strange. He said, 'All right.'

Let's go and watch." Wei's "all right" meant that all would be in

accordance with tradition, in which case it was not worth watching;

still, they wanted to look on, and after dusk the hall filled with

light-hearted spectators.

我也是去看的一個,先送了一份香燭;待到走到他家,已見連殳在給死者穿衣服了。原來他是一個短小瘦削的人,長方臉,蓬鬆的頭髮和濃黑的鬚眉佔了一臉的小半,只見兩眼在黑氣里發光。那穿衣也穿得真好,井井有條,彷彿是一個大殮的專家,使旁觀者不覺嘆服。寒石山老例,當這些時候,無論如何,母家的親丁是總要挑剔的;他卻只是默默地,遇見怎麼挑剔便怎麼改,神色也不動。站在我前面的一個花白頭髮的老太太,便發出羨慕感嘆的聲音。

I was one of those who went, having first sent along my gift of incense

and candles. As I arrived he was already putting the shroud on the dead.

He was a thin man with an angular face, hidden to a certain extent by

his dishevelled hair, dark eyebrows and moustache. His eyes gleamed

darkly. He laid out the body very well, as deftly as an expert, so that

the spectators were impressed. According to the local custom, at a

married woman's funeral members of the dead woman's family found fault

even when everything was well done; however, he remained silent,

complying with their wishes with a face devoid of all expression. An

old, grey-haired woman standing before me gave a sigh of envy and

respect.

其次是拜;其次是哭,凡女人們都念念有詞。其次入棺;其次又是拜;又是哭,直到釘好了棺蓋。沉靜了一瞬間,大家忽而擾動了,很有驚異和不滿的形勢。我也不由的突然覺到:連殳就始終沒有落過一滴淚,只坐在草荐上,兩眼在黑氣里閃閃地發光。

People kowtowed; then they wailed, all the women chanting as they

wailed. When the body was put in the coffin, all kowtowed again, then

wailed again, until the lid of the coffin was nailed down. Silence

reigned for a moment, and then there was a stir of surprise and

dissatisfaction. I too suddenly realized that from beginning to end Wei

had not shed a single tear. He was simply sitting on the mourner's mat,

his two eyes gleaming darkly.

大殮便在這驚異和不滿的空氣裡面完畢。大家都怏怏地,似乎想走散,但連殳卻還坐在草荐上沉思。忽然,他流下淚來了,接著就失聲,立刻又變成長嚎,像一匹受傷的狼,當深夜在曠野中嗥叫,慘傷里夾雜著憤怒和悲哀。這模樣,是老例上所沒有的,先前也未曾豫防到,大家都手足無措了,遲疑了一會,就有幾個人上前去勸止他,愈去愈多,終於擠成一大堆。但他卻只是兀坐著號啕,鐵塔似的動也不動。

In this atmosphere of surprise and dissatisfaction, the ceremony ended.

The disgruntled mourners seemed about to leave, but Wei was still

sitting on the mat, lost in thought. Suddenly, tears fell from his eyes,

then he burst into a long wail like a wounded wolf howling in the

wilderness in the dead of night, anger and sorrow mingled with his

agony. This was not in accordance with tradition and, taken by surprise,

we were at a loss. After a little hesitation, some went to try to

persuade him to stop, and these were joined by more and more people

until finally there was a crowd round him. But he sat there wailing,

motionless as an iron statue.

大家又只得無趣地散開;他哭著,哭著,約有半點鐘,這才突然停了下來,也不向弔客招呼,徑自往家裡走。接著就有前去窺探的人來報告:他走進他祖母的房裡,躺在床上,而且,似乎就睡熟了。

Feeling awkward, the crowd dispersed. Wei continued to cry for about

half an hour, then suddenly stopped, and without a word to the mourners

went straight inside. Later it was reported by spies that he had gone

into his grandmother's room, lain down on the bed and, to all

appearances, fallen sound asleep.

隔了兩日,是我要動身回城的前一天,便聽到村人都遭了魔似的發議論,說連殳要將所有的器具大半燒給他祖母,餘下的便分贈生時侍奉,死時送終的女工,並且連房屋也要無期地借給她居住了。親戚本家都說到舌敝唇焦,也終於阻當不住。

Two days later, on the eve of my return to town, I heard the villagers

discussing eagerly, as if they were possessed, how Wei intended to burn

most of his dead grandmother's furniture and possessions, giving the

rest to the maidservant who had served her during her life and attended

her on her deathbed. Even the house was to be lent to the maid for an

indefinite period. Wei's relatives argued themselves hoarse, but could

not shake his resolution.

恐怕大半也還是因為好奇心,我歸途中經過他家的門口,便又順便去弔慰。他穿了毛邊的白衣出見,神色也還是那樣,冷冷的。我很勸慰了一番;他卻除了唯唯諾諾之外,只回答了一句話,是:

「多謝你的好意。」

On my way back, largely out of curiosity perhaps, I passed his house and went in to express condolence. He received me wearing a hemless white mourning dress, and his expression was as cold as ever. I urged him not to take it so to heart, but apart from grunting noncommittally all he said was:

"Thanks for your concern."

二

我們第三次相見就在這年的冬初,S城的一個書鋪子里,大家同時點了一點頭,總算是認識了。但使我們接近起來的,是在這年底我失了職業之後。從此,我便常常訪問連殳去。一則,自然是因為無聊賴;二則,因為聽人說,他倒很親近失意的人的,雖然素性這麼冷。但是世事升沉無定,失意人也不會我一投名片,他便接見了。兩間連通的客廳,並無什麼陳設,不過是桌椅之外,排列些書架,大家雖說他是一個可怕的「新黨」,架上卻不很有新書。他已經知道我失了職業;但套話一說就完,主客便只好默默地相對,逐漸沉悶起來。我只見他很快地吸完一枝煙,煙蒂要燒著手指了,才拋在地面上。

Early that winter we met for the third time. It was in a bookshop in

S——, where we nodded simultaneously, showing at least that we were

acquainted. But it was at the end of that year, after I lost my job,

that we became friends. Thenceforward I paid Wei many visits. In the

first place, of course, I had nothing to do; in the second place,

despite his habitual reserve, he was said to sympathize with lame dogs.

However, fortune being fickle, lame dogs do not remain lame for ever,

hence he had few steady friends. Report proved true, for as soon as I

sent in my card, he received me. His sitting-room consisted of two rooms

thrown into one, quite bare of ornament, with nothing in it apart from

table and chairs, but some bookcases. Although he was reputed to be

terribly "modern," there were few modern books on the shelves. He knew

that I had lost my job; but after the usual polite remarks had been

exchanged, host and guest sat silent, with nothing to say to each other.

I noticed he very quickly finished his cigarette, only dropping it to

the ground when it nearly burned his fingers.

「吸煙罷。」他伸手取第二枝煙時,忽然說。

我便也取了一枝,吸著,講些關於教書和書籍的,但也還覺得沉悶。我正想走時,門外一陣喧嚷和腳步聲,四個男女孩子闖進來了。大的八九歲,小的四五歲,手臉和衣服都很臟,而且丑得可以。但是連殳的眼裡卻即刻發出歡喜的光來了,連忙站起,向客廳間壁的房裡走,一面說道:

「大良,二良,都來!你們昨天要的口琴,我已經買來了。」

我便也取了一枝,吸著,講些關於教書和書籍的,但也還覺得沉悶。我正想走時,門外一陣喧嚷和腳步聲,四個男女孩子闖進來了。大的八九歲,小的四五歲,手臉和衣服都很臟,而且丑得可以。但是連殳的眼裡卻即刻發出歡喜的光來了,連忙站起,向客廳間壁的房裡走,一面說道:

「大良,二良,都來!你們昨天要的口琴,我已經買來了。」

"Have a cigarette," he said suddenly, reaching for another.

I took one and, between puffs, spoke of teaching and books, still finding very little to say. I was just thinking of leaving when I heard shouts and footsteps outside the door, and four children rushed in. The eldest was about eight or nine, the smallest four or five. Their hands, faces and clothes were very dirty, and they were thoroughly unprepossessing; yet Wei's face lit up with pleasure, and getting up at once he walked to the other room, saying:

"Come, Ta-liang, Erh-liang, all of you! I have bought the mouth-organs you wanted yesterday."

I took one and, between puffs, spoke of teaching and books, still finding very little to say. I was just thinking of leaving when I heard shouts and footsteps outside the door, and four children rushed in. The eldest was about eight or nine, the smallest four or five. Their hands, faces and clothes were very dirty, and they were thoroughly unprepossessing; yet Wei's face lit up with pleasure, and getting up at once he walked to the other room, saying:

"Come, Ta-liang, Erh-liang, all of you! I have bought the mouth-organs you wanted yesterday."

孩子們便跟著一齊擁進去,立刻又各人吹著一個口琴一擁而出,一出客廳門,不知怎的便打將起來。有一個哭了。

「一人一個,都一樣的。不要爭呵!」他還跟在後面囑咐。

「這麼多的一群孩子都是誰呢?」我問。

「是房主人的。他們都沒有母親,只有一個祖母。」

「房東只一個人么?」

「是的。他的妻子大概死了三四年了罷,沒有續娶。——否則,便要不肯將余屋租給我似的單身人。」他說著,冷冷地微笑了。

「一人一個,都一樣的。不要爭呵!」他還跟在後面囑咐。

「這麼多的一群孩子都是誰呢?」我問。

「是房主人的。他們都沒有母親,只有一個祖母。」

「房東只一個人么?」

「是的。他的妻子大概死了三四年了罷,沒有續娶。——否則,便要不肯將余屋租給我似的單身人。」他說著,冷冷地微笑了。

The children rushed in after him, to return immediately with a

mouth-organ apiece; but once outside they started fighting, and one of

them cried.

"There's one each; they're exactly the same. Don't squabble!" he said as he followed them.

"Whose children are they?" I asked.

"The landlord's. They have no mother, only a grandmother."

"Your landlord is a widower?"

"Yes. His wife died three or four years ago, and he has not remarried. Otherwise, he would not rent his spare rooms to a bachelor like me." He said this with a cold smile.

"There's one each; they're exactly the same. Don't squabble!" he said as he followed them.

"Whose children are they?" I asked.

"The landlord's. They have no mother, only a grandmother."

"Your landlord is a widower?"

"Yes. His wife died three or four years ago, and he has not remarried. Otherwise, he would not rent his spare rooms to a bachelor like me." He said this with a cold smile.

我很想問他何以至今還是單身,但因為不很熟,終於不好開口。

只要和連殳一熟識,是很可以談談的。他議論非常多,而且往往頗奇警。使人不耐的倒是他的有些來客,大抵是讀過《沉淪》〔4〕的罷,時常自命為「不幸的青年」或是「零餘者」,螃蟹一般懶散而驕傲地堆在大椅子上,一面唉聲嘆氣,一面皺著眉頭吸煙。還有那房主的孩子們,總是互相爭吵,打翻碗碟,硬討點心,亂得人頭昏。但連殳一見他們,卻再不像平時那樣的冷冷的了,看得比自己的性命還寶貴。聽說有一回,三良發了紅斑痧,竟急得他臉上的黑氣愈見其黑了;不料那病是輕的,於是後來便被孩子們的祖母傳作笑柄。

只要和連殳一熟識,是很可以談談的。他議論非常多,而且往往頗奇警。使人不耐的倒是他的有些來客,大抵是讀過《沉淪》〔4〕的罷,時常自命為「不幸的青年」或是「零餘者」,螃蟹一般懶散而驕傲地堆在大椅子上,一面唉聲嘆氣,一面皺著眉頭吸煙。還有那房主的孩子們,總是互相爭吵,打翻碗碟,硬討點心,亂得人頭昏。但連殳一見他們,卻再不像平時那樣的冷冷的了,看得比自己的性命還寶貴。聽說有一回,三良發了紅斑痧,竟急得他臉上的黑氣愈見其黑了;不料那病是輕的,於是後來便被孩子們的祖母傳作笑柄。

I wanted very much to ask why he had remained single so long, but I did not know him well enough.

Once you knew him well, he was a good talker. He was full of ideas, many of them quite remarkable. What exasperated me were some of his guests. As a result, probably, of reading Yu Ta-fu's romantic stories,1 they constantly referred to themselves as "the young unfortunate" or "the outcast"; and, sprawling on the big chairs like lazy and arrogant crabs, they would sigh, smoke and frown all at the same time.

Once you knew him well, he was a good talker. He was full of ideas, many of them quite remarkable. What exasperated me were some of his guests. As a result, probably, of reading Yu Ta-fu's romantic stories,1 they constantly referred to themselves as "the young unfortunate" or "the outcast"; and, sprawling on the big chairs like lazy and arrogant crabs, they would sigh, smoke and frown all at the same time.

Then there were the landlord's children, who always fought among themselves, knocked over bowls and plates, begged for cakes and kept up an ear-splitting din. Yet the sight of them invariably dispelled Wei's customary coldness, and they seemed to be the most precious thing in his life. Once the third child was said to have measles. He was so worried that his dark face took on an even darker hue. The attack proved a light one, however, and thereafter the children's grandmother made a joke of his anxiety.

「孩子總是好的。他們全是天真……。」他似乎也覺得我有些不耐煩了,有一天特地乘機對我說。

「那也不盡然。」我只是隨便回答他。

「不。大人的壞脾氣,在孩子們是沒有的。後來的壞,如你平日所攻擊的壞,那是環境教壞的。原來卻並不壞,天真……。我以為中國的可以希望,只在這一點。」

「不。如果孩子中沒有壞根苗,大起來怎麼會有壞花果?譬如一粒種子,正因為內中本含有枝葉花果的胚,長大時才能夠發出這些東西來。何嘗是無端……。」我因為閑著無事,便也如大人先生們一下野,就要吃素談禪〔5〕一樣,正在看佛經。佛理自然是並不懂得的,但竟也不自檢點,一味任意地說。

然而連殳氣忿了,只看了我一眼,不再開口。我也猜不出他是無話可說呢,還是不屑辯。但見他又顯出許久不見的冷冷的態度來,默默地連吸了兩枝煙;待到他再取第三枝時,我便只好逃走了。

這仇恨是歷了三月之久才消釋的。原因大概是一半因為忘卻,一半則他自己竟也被「天真」的孩子所仇視了,於是覺得我對於孩子的冒瀆的話倒也情有可原。但這不過是我的推測。其時是在我的寓里的酒後,他似乎微露悲哀模樣,半仰著頭道:

「想起來真覺得有些奇怪。我到你這裡來時,街上看見一個很小的小孩,拿了一片蘆葉指著我道:殺!他還不很能走路……。」

「這是環境教壞的。」

我即刻很後悔我的話。但他卻似乎並不介意,只竭力地喝酒,其間又竭力地吸煙。

「我倒忘了,還沒有問你,」我便用別的話來支梧,「你是不大訪問人的,怎麼今天有這興緻來走走呢?我們相識有一年多了,你到我這裡來卻還是第一回。」

「我正要告訴你呢:你這幾天切莫到我寓里來看我了。我的寓里正有很討厭的一大一小在那裡,都不像人!」

「一大一小?這是誰呢?」我有些詫異。

「是我的堂兄和他的小兒子。哈哈,兒子正如老子一般。」

「是上城來看你,帶便玩玩的罷?」

「不。說是來和我商量,就要將這孩子過繼給我的。」

「呵!過繼給你?」我不禁驚叫了,「你不是還沒有娶親么?」

「他們知道我不娶的了。但這都沒有什麼關係。他們其實是要過繼給我那一間寒石山的破屋子。我此外一無所有,你是知道的;錢一到手就化完。只有這一間破屋子。他們父子的一生的事業是在逐出那一個借住著的老女工。」

他那詞氣的冷峭,實在又使我悚然。但我還慰解他說:

「我看你的本家也還不至於此。他們不過思想略舊一點罷了。譬如,你那年大哭的時候,他們就都熱心地圍著使勁來勸你……。」

「我父親死去之後,因為奪我屋子,要我在筆據上畫花押,我大哭著的時候,他們也是這樣熱心地圍著使勁來勸我……。」他兩眼向上凝視,彷彿要在空中尋出那時的情景來。

「總而言之:關鍵就全在你沒有孩子。你究竟為什麼老不結婚的呢?」我忽而尋到了轉舵的話,也是久已想問的話,覺得這時是最好的機會了。

他詫異地看著我,過了一會,眼光便移到他自己的膝髁上去了,於是就吸煙,沒有回答。

Apparently sensing my impatience, he seized an opening one day to say, "Children are always good. They are all so innocent. . . . ."

"Not always," I answered casually.

"Always. Children have none of the faults of grown-ups. If they turn out badly later, as you contend, it is because they have been moulded by their environment. Originally they are nor bad, but innocent. . . . I think China's only hope lies in this."

"I don't agree. Without the root of evil, how could they bear evil fruit in later life? Take a seed, for example. It is because it contains the embryo leaves, flowers and fruits, that later it grows into these things. There must be a cause. . . ." Since my unemployment, just like those great officials who resigned from office and took up Buddhism, I had been reading the Buddhist sutras. I did not understand Buddhist philosophy though, and was just talking at random.

However, Wei was annoyed. He gave me a look, then said no more. I could nor tell whether he had no more to say, or whether he felt it not worth arguing with me. But he looked cold again, as he had nor done for a long time, and smoked two cigarettes one after the other in silence. By the time he reached for the third cigarette, I beat a retreat.

Our estrangement lasted three months. Then, owing in part to forgetfulness, in part to the fact that he fell out with those "innocent" children, he came to consider my slighting remarks on children as excusable. Or so I surmised. This happened in my house after drinking one day, when, with a rather melancholy look, he cocked his head and said:

"Come to think of it, it's really curious. On my way here I met a small child with a reed in his hand, which he pointed at me, shouting, 'Kill!' He was just a toddler. . . ."

"He must have been moulded by his environment."

As soon as I had said this, I wanted to take it back. However, he did not seem to care, just went on drinking heavily, smoking furiously in between.

"I meant to ask you," I said, trying to change the subject. "You don't usually call on people, what made you come out today? I've known you for more than a year, yet this is the first time you've been here."

"I was just going to tell you: don't call on me for the time being. There are a father and son in my place who are perfect pests. They are scarcely human!"

"Father and son? Who are they?" I was surprised.

"My cousin and his son. Well, the son resembles the father."

"I suppose they came to town to see you and have a good time?"

"No. They came to talk me into adopting the boy."

"What, to adopt the boy?" I exclaimed in amazement. "But you are not married."

"They know I won't marry. But that's nothing to them. Actually they want to inherit that tumbledown house of mine in the village. I have no other property, you know; as soon as I get money I spend it. I've only that house. Their purpose in life is to drive out the old maidservant who is living in the place for the time being."

The cynicism of his remark took me aback. However I tried to soothe him, by saying:

"I don't think your relatives can be so bad. They are only rather old-fashioned. For instance, that year when you cried bitterly, they came forward eagerly to plead with you.

"When I was a child and my father died, I cried bitterly because they wanted to take the house from me and make me put my mark on the document. They came forward eagerly then to plead with me. . . ." He looked up, as if searching the air for that bygone scene.

"The crux of the matter is—you have no children. Why don't you get married?" I had found a way to change the subject, and this was something I had been wanting to ask for a long time. It seemed an excellent opportunity.

He looked at me in surprise, then dropped his gaze to his knees, and started smoking. I received no answer to my question.

三

但是,雖在這一種百無聊賴的境地中,也還不給連殳安住。漸漸地,小報上有匿名人來攻擊他,學界上也常有關於他的流言,可是這已經並非先前似的單是話柄,大概是於他有損的了。我知道這是他近來喜歡發表文章的結果,倒也並不介意。S城人最不願意有人發些沒有顧忌的議論,一有,一定要暗暗地來叮他,這是向來如此的,連殳自己也知道。但到春天,忽然聽說他已被校長辭退了。這卻使我覺得有些兀突;其實,這也是向來如此的,不過因為我希望著自己認識的人能夠倖免,所以就以為兀突罷了,S城人倒並非這一回特別惡。

其時我正忙著自己的生計,一面又在接洽本年秋天到山陽去當教員的事,竟沒有工夫去訪問他。待到有些餘暇的時候,離他被辭退那時大約快有三個月了,可是還沒有發生訪問連殳的意思。有一天,我路過大街,偶然在舊書攤前停留,卻不禁使我覺到震悚,因為在那裡陳列著的一部汲古閣初印本《史記索隱》〔6〕,正是連殳的書。他喜歡書,但不是藏書家,這種本子,在他是算作貴重的善本,非萬不得已,不肯輕易變賣的。難道他失業剛才兩三月,就一貧至此么?雖然他向來一有錢即隨手散去,沒有什麼貯蓄。於是我便決意訪問連殳去,順便在街上買了一瓶燒酒,兩包花生米,兩個熏魚頭。

他的房門關閉著,叫了兩聲,不見答應。我疑心他睡著了,更加大聲地叫,並且伸手拍著房門。

「出去了罷!」大良們的祖母,那三角眼的胖女人,從對面的窗口探出她花白的頭來了,也大聲說,不耐煩似的。

「那裡去了呢?」我問。

「那裡去了?誰知道呢?——他能到那裡去呢,你等著就是,一會兒總會回來的。」

我便推開門走進他的客廳去。真是「一日不見,如隔三秋」〔7〕,滿眼是凄涼和空空洞洞,不但器具所余無幾了,連書籍也只剩了在S城決沒有人會要的幾本洋裝書。屋中間的圓桌還在,先前曾經常常圍繞著憂鬱慷慨的青年,懷才不遇的奇士和腌臟吵鬧的孩子們的,現在卻見得很閑靜,只在面上蒙著一層薄薄的灰塵。我就在桌上放了酒瓶和紙包,拖過一把椅子來,靠桌旁對著房門坐下。

的確不過是「一會兒」,房門一開,一個人悄悄地陰影似的進來了,正是連殳。也許是傍晚之故罷,看去彷彿比先前黑,但神情卻還是那樣。

「阿!你在這裡?來得多久了?」他似乎有些喜歡。

「並沒有多久。」我說,「你到那裡去了?」

「並沒有到那裡去,不過隨便走走。」

他也拖過椅子來,在桌旁坐下;我們便開始喝燒酒,一面談些關於他的失業的事。但他卻不願意多談這些;他以為這是意料中的事,也是自己時常遇到的事,無足怪,而且無可談的。他照例只是一意喝燒酒,並且依然發些關於社會和歷史的議論。不知怎地我此時看見空空的書架,也記起汲古閣初印本的《史記索隱》,忽而感到一種淡漠的孤寂和悲哀。

「你的客廳這麼荒涼……。近來客人不多了么?」

「沒有了。他們以為我心境不佳,來也無意味。心境不佳,實在是可以給人們不舒服的。冬天的公園,就沒有人去……。」

他連喝兩口酒,默默地想著,突然,仰起臉來看著我問道,「你在圖謀的職業也還是毫無把握罷?……」

我雖然明知他已經有些酒意,但也不禁憤然,正想發話,只見他側耳一聽,便抓起一把花生米,出去了。門外是大良們笑嚷的聲音。

但他一出去,孩子們的聲音便寂然,而且似乎都走了。他還追上去,說些話,卻不聽得有回答。他也就陰影似的悄悄地回來,仍將一把花生米放在紙包里。

「連我的東西也不要吃了。」他低聲,嘲笑似的說。

「連殳,」我很覺得悲涼,卻強裝著微笑,說,「我以為你太自尋苦惱了。你看得人間太壞……。」

他冷冷的笑了一笑。

「我的話還沒有完哩。你對於我們,偶而來訪問你的我們,也以為因為閑著無事,所以來你這裡,將你當作消遣的資料的罷?」

「並不。但有時也這樣想。或者尋些談資。」

「那你可錯誤了。人們其實並不這樣。你實在親手造了獨頭繭〔8〕,將自己裹在裡面了。你應該將世間看得光明些。」我嘆惜著說。

「也許如此罷。但是,你說:那絲是怎麼來的?——自然,世上也盡有這樣的人,譬如,我的祖母就是。我雖然沒有分得她的血液,卻也許會繼承她的運命。然而這也沒有什麼要緊,我早已豫先一起哭過了……。」

我即刻記起他祖母大殮時候的情景來,如在眼前一樣。

「我總不解你那時的大哭……。」於是鶻突地問了。

「我的祖母入殮的時候罷?是的,你不解的。」他一面點燈,一面冷靜地說,「你的和我交往,我想,還正因為那時的哭哩。你不知道,這祖母,是我父親的繼母;他的生母,他三歲時候就死去了。」他想著,默默地喝酒,吃完了一個熏魚頭。

「那些往事,我原是不知道的。只是我從小時候就覺得不可解。那時我的父親還在,家景也還好,正月間一定要懸掛祖像,盛大地供養起來。看著這許多盛裝的畫像,在我那時似乎是不可多得的眼福。但那時,抱著我的一個女工總指了一幅像說:『這是你自己的祖母。拜拜罷,保佑你生龍活虎似的大得快。』我真不懂得我明明有著一個祖母,怎麼又會有什麼『自己的祖母』來。可是我愛這『自己的祖母』,她不比家裡的祖母一般老;她年青,好看,穿著描金的紅衣服,戴著珠冠,和我母親的像差不多。我看她時,她的眼睛也注視我,而且口角上漸漸增多了笑影:我知道她一定也是極其愛我的。

「然而我也愛那家裡的,終日坐在窗下慢慢地做針線的祖母。雖然無論我怎樣高興地在她面前玩笑,叫她,也不能引她歡笑,常使我覺得冷冷地,和別人的祖母們有些不同。但我還愛她。可是到後來,我逐漸疏遠她了;這也並非因為年紀大了,已經知道她不是我父親的生母的緣故,倒是看久了終日終年的做針線,機器似的,自然免不了要發煩。但她卻還是先前一樣,做針線;管理我,也愛護我,雖然少見笑容,卻也不加呵斥。直到我父親去世,還是這樣;後來呢,我們幾乎全靠她做針線過活了,自然更這樣,直到我進學堂……。」

燈火銷沉下去了,煤油已經將涸,他便站起,從書架下摸出一個小小的洋鐵壺來添煤油。

「只這一月里,煤油已經漲價兩次了……。」他旋好了燈頭,慢慢地說。「生活要日見其困難起來。——她後來還是這樣,直到我畢業,有了事做,生活比先前安定些;恐怕還直到她生病,實在打熬不住了,只得躺下的時候罷……。

「她的晚年,據我想,是總算不很辛苦的,享壽也不小了,正無須我來下淚。況且哭的人不是多著么?連先前竭力欺凌她的人們也哭,至少是臉上很慘然。哈哈!……可是我那時不知怎地,將她的一生縮在眼前了,親手造成孤獨,又放在嘴裡去咀嚼的人的一生。而且覺得這樣的人還很多哩。這些人們,就使我要痛哭,但大半也還是因為我那時太過於感情用事……。

「你現在對於我的意見,就是我先前對於她的意見。然而我的那時的意見,其實也不對的。便是我自己,從略知世事起,就的確逐漸和她疏遠起來了……。」

他沉默了,指間夾著煙捲,低了頭,想著。燈火在微微地發抖。

「呵,人要使死後沒有一個人為他哭,是不容易的事呵。」

他自言自語似的說;略略一停,便仰起臉來向我道,「想來你也無法可想。我也還得趕緊尋點事情做……。」

「你再沒有可托的朋友了么?」我這時正是無法可想,連自己。

「那倒大概還有幾個的,可是他們的境遇都和我差不多……。」

我辭別連殳出門的時候,圓月已經升在中天了,是極靜的夜。

III

Yet he was not allowed to enjoy even this inane existence in peace. Gradually anonymous attacks appeared in the less reputable papers, and rumours concerning him were spread in the schools. This was not the simple gossip of the old days, but deliberately damaging. I knew this was the outcome of articles he had taken to writing for magazines, so I paid no attention. The citizens of S—— disliked nothing more than fearless argument, and anyone guilty of it indubitably became the object of secret attacks. This was the rule, and Wei knew it too. However, in spring, when I heard he had been asked by the school authorities to resign, I confessed it surprised me. Of course, this was only to be expected, and it surprised me simply because I had hoped my friend would escape. The citizens of S—— were not proving more vicious than usual.

I was occupied then with my own problems, negotiating to go to a school in Shanyang that autumn, so I had no time to call on him. Some three months passed before I was at leisure, and even then it had not occurred to me to visit him. One day, passing the main street, I happened to pause before a secondhand bookstall, where I was startled to see an early edition of the Commentaries on Ssuma Chien's "Historical Records"2 from Wei's collection on display. He was no connoisseur, but he loved books, and I knew he prized this particular one. He must be very hard pressed to have sold it. It seemed scarcely possible he could have become so poor only two or three months after losing his job; yet he spent money as soon as he had it, and had never saved. I decided to call on him. On the same street I bought a bottle of liquor, two packages of peanuts and two smoked fish-heads.

His door was closed. I called out twice, but there was no reply. Thinking he was asleep, I called louder, at the same time hammering on the door.

"He's probably out." The children's grandmother, a fat woman with small eyes, thrust her grey head our from the opposite window, and spoke impatiently.

"Where has he gone?" I asked.

"Where? Who knows—where could he go? You can wait, he will be back soon."

I pushed open the door and went into his sitting-room. It was greatly changed, looking desolate in its emptiness. There was little furniture left, while all that remained of his library were those foreign books which could not be sold. The middle of the room was still occupied by the table around which those woeful and gallant young men, unrecognized geniuses, and dirty, noisy children had formerly gathered. Now it all seemed very quiet, and there was a thin layer of dust on the table. I put the bottle and packages down, pulled over a chair, and sat down by the table facing the door.

Very soon, sure enough, the door opened, and someone stepped in as silently as a shadow. It was Wei. It might have been the twilight that made his face look dark; but his expression was unchanged.

"Ah, it's you? How long have you been here?" He seemed pleased.

"Not very long," I said. "Where have you been?"

"Nowhere in particular. Just taking a stroll."

He pulled up a chair too and sat by the table. We started drinking, and spoke of his losing his job. However, he did not care to talk much about it, considering it only to be expected. He had come across many similar cases. It was not strange at all, and nor worth discussing. As usual, he drank heavily, and discoursed on society and the study of history. Something made me glance at the empty bookshelves, and, remembering the Commentaries on Ssuma Chien's "Historical Records", I was conscious of a slight loneliness and sadness.

"Your sitting-room has a deserted look

Have you had fewer visitors recently?"

"None at all. They don't find it much fun when I'm not in a good mood. A bad mood certainly makes people uncomfortable Just as no one goes to the park in winter. . . ."

He took two sips of liquor in succession, then fell silent. Suddenly, looking up, he asked, "I suppose you have had no luck either in finding work?"

Although I knew he was only venting his feelings as a result of drinking, I felt indignant at the way people treated him. Just as I was about to say something, he pricked up his ears, then, scooping up some peanuts, went our. Outside, I could hear the laughter and shouts of the children.

But as soon as he went out, the children became quiet. It sounded as if they had left. He went after them, and said something, but I could hear no reply. Then, as silent as a shadow, he came back and put the handful of peanuts back in the package.

"They don't even want to eat anything I give them," he said sarcastically, in a low voice.

"Old Wei," I said, forcing a smile, although I was sick at heart, "I think you are tormenting yourself unnecessarily. Why think so poorly of your fellow men?"

He only smiled cynically.

"I haven't finished yet. I suppose you consider people like me, who come here occasionally, do so in order to kill time or amuse themselves at your expense?"

"No, I don't. Well, sometimes I do. Perhaps they come to find something to talk about."

"Then you are wrong. People are not like that. You are really wrapping yourself up in a cocoon. You should take a more cheerful view." I sighed.

"Maybe. But tell me, where does the thread for the cocoon come from? Of course, there are plenty of people like that; take my grandmother, for example. Although I have none of her blood in my veins, I may inherit her fate. But that doesn't matter, I have already bewailed my fate together with hers. . . ."

Then I remembered what had happened at his grandmother's funeral. I could almost see it before my eyes.

"I still don't understand why you cried so bitterly," I said bluntly.

"You mean at my grandmother's funeral? No, you wouldn't." He lit the lamp. "I suppose it was because of that that we became friends," he said quietly. "You know, this grandmother was my grandfather's second wife. My father's own mother died when he was three." Growing thoughtful, he drank silently, and finished a smoked fish-head.

"I didn't know it to begin with. Only, from my childhood I was puzzled. Ar that time my father was still alive, and our family was well off. During the lunar New Year we would hang up the ancestral images and hold a grand sacrifice. It was one of my rare pleasures to look at those splendidly dressed images. At that time a maidservant would always carry me to an image, and point at it, saying: 'This is your own grandmother. Bow to her so that she will protect you and make you grow up strong and healthy.' I could not understand how I came to have another grandmother, in addition to the one beside me. But I liked this grandmother who was 'my own.' She was not as old as the granny at home. Young and beautiful, wearing a red costume with golden embroidery and a headdress decked with pearls, she resembled my mother. When I looked at her, her eyes seemed to gaze down on me, and a faint smile appeared on her lips. I knew she was very fond of me too.

"But I liked the granny at home too, who sat all day under the window slowly plying her needle. However, no matter how merrily I laughed and played in front of her, or called to her, I could not make her laugh; and that made me feel she was cold, unlike other children's grandmothers. Still, I liked her. Later on, though, I gradually cooled towards her, nor because I grew older and learned she was not my own grandmother, but rather because I was exasperated by the way she kept on sewing mechanically, day in, day our. She was unchanged, however. She sewed, looked after me, loved and protected me as before; and though she seldom smiled, she never scolded me. It was the same after my father died. Later on, we lived almost entirely on her sewing, so it was still the same, until I went to school. . . ."

The light flickered as the paraffin gave out, and he stood up to refill the lamp from a small tin kettle under the bookcase.

"The price of paraffin has gone up twice this month," he said slowly, after turning up the wick. "Life becomes harder every day. She remained the same until I graduated from school and had a job, when our life became more secure. She didn't change, I suppose, until she was sick, couldn't carry on, and had to take to her bed. . . .

"Since her later days, I think, were not too unhappy on the whole, and she lived to a great age, I need not have mourned. Besides, weren't there a lot of others there eager to wail? Even those who had tried their hardest to rob her, wailed, or appeared bowed down with grief." He laughed. "However, at that moment her whole life rose to my mind—the life of one who created loneliness for herself and tasted its bitterness. I felt there were many people like that. I wanted to weep for them; but perhaps it was largely because I was too sentimental. . . .

"Your present advice to me is what I felt with regard to her. But actually my ideas at that time were wrong. As for myself, since I grew up my feelings for her cooled. . . ."

He paused, with a cigarette between his fingers; and bending his head lost himself in thought. The lamplight flickered.

"Well, it is hard to live so that no one will mourn for your death," he said, as if to himself. After a pause he looked up at me, and said, "I suppose you can't help? I shall have to find something to do very soon."

"Have you no other friends you could ask?" I was in no position to help myself then, let alone others.

"I have a few, but they are all in the same boat. . . ."

When I left him, the full moon was high in the sky and the night was very still.

四

山陽的教育事業的狀況很不佳。我到校兩月,得不到一文薪水,只得連煙捲也節省起來。但是學校里的人們,雖是月薪十五六元的小職員,也沒有一個不是樂天知命的,仗著逐漸打熬成功的銅筋鐵骨,面黃肌瘦地從早辦公一直到夜,其間看見名位較高的人物,還得恭恭敬敬地站起,實在都是不必「衣食足而知禮節」〔8〕的人民。我每看見這情狀,不知怎的總記起連殳臨別託付我的話來。他那時生計更其不堪了,窘相時時顯露,看去似乎已沒有往時的深沉,知道我就要動身,深夜來訪,遲疑了許久,才吞吞吐吐地說道:

「不知道那邊可有法子想?——便是鈔寫,一月二三十塊錢的也可以的。我……。」

我很詫異了,還不料他竟肯這樣的遷就,一時說不出話來。

「我……,我還得活幾天……。」

「那邊去看一看,一定竭力去設法罷。」

這是我當日一口承當的答話,後來常常自己聽見,眼前也同時浮出連殳的相貌,而且吞吞吐吐地說道「我還得活幾天」。到這些時,我便設法向各處推薦一番;但有什麼效驗呢,事少人多,結果是別人給我幾句抱歉的話,我就給他幾句抱歉的信。到一學期將完的時候,那情形就更加壞了起來。那地方的幾個紳士所辦的《學理周報》上,竟開始攻擊我了,自然是決不指名的,但措辭很巧妙,使人一見就覺得我是在挑剔學潮〔10〕,連推薦連殳的事,也算是呼朋引類。

我只好一動不動,除上課之外,便關起門來躲著,有時連煙捲的煙鑽出窗隙去,也怕犯了挑剔學潮的嫌疑。連殳的事,自然更是無從說起了。這樣地一直到深冬。

下了一天雪,到夜還沒有止,屋外一切靜極,靜到要聽出靜的聲音來。我在小小的燈火光中,閉目枯坐,如見雪花片片飄墜,來增補這一望無際的雪堆;故鄉也準備過年了,人們忙得很;我自己還是一個兒童,在後園的平坦處和一夥小朋友塑雪羅漢。雪羅漢的眼睛是用兩塊小炭嵌出來的,顏色很黑,這一閃動,便變了連殳的眼睛。

「我還得活幾天!」仍是這樣的聲音。

「為什麼呢?」我無端地這樣問,立刻連自己也覺得可笑了。

這可笑的問題使我清醒,坐直了身子,點起一枝煙捲來;推窗一望,雪果然下得更大了。聽得有人叩門;不一會,一個人走進來,但是聽熟的客寓雜役的腳步。他推開我的房門,交給我一封六寸多長的信,字跡很潦草,然而一瞥便認出「魏緘」兩個字,是連殳寄來的。

這是從我離開S城以後他給我的第一封信。我知道他疏懶,本不以杳無消息為奇,但有時也頗怨他不給一點消息。待到接了這信,可又無端地覺得奇怪了,慌忙拆開來。裡面也用了一樣潦草的字體,寫著這樣的話:

「申飛……。

「我稱你什麼呢?我空著。你自己願意稱什麼,你自己添上去罷。我都可以的。

「別後共得三信,沒有復。這原因很簡單:我連買郵票的錢也沒有。

「你或者願意知道些我的消息,現在簡直告訴你罷:我失敗了。先前,我自以為是失敗者,現在知道那並不,現在才真是失敗者了。先前,還有人願意我活幾天,我自己也還想活幾天的時候,活不下去;現在,大可以無須了,然而要活下去……。

「然而就活下去么?

「願意我活幾天的,自己就活不下去。這人已被敵人誘殺了。誰殺的呢?誰也不知道。

「人生的變化多麼迅速呵!這半年來,我幾乎求乞了,實際,也可以算得已經求乞。然而我還有所為,我願意為此求乞,為此凍餒,為此寂寞,為此辛苦。但滅亡是不願意的。你看,有一個願意我活幾天的,那力量就這麼大。然而現在是沒有了,連這一個也沒有了。同時,我自己也覺得不配活下去;別人呢?也不配的。同時,我自己又覺得偏要為不願意我活下去的人們而活下去;好在願意我好好地活下去的已經沒有了,再沒有誰痛心。使這樣的人痛心,我是不願意的。然而現在是沒有了,連這一個也沒有了。快活極了,舒服極了;我已經躬行我先前所憎惡,所反對的一切,拒斥我先前所崇仰,所主張的一切了。我已經真的失敗,——然而我勝利了。

「你以為我發了瘋么?你以為我成了英雄或偉人了么?不,不的。這事情很簡單;我近來已經做了杜師長的顧問,每月的薪水就有現洋八十元了。

「申飛……。

「你將以我為什麼東西呢,你自己定就是,我都可以的。

「你大約還記得我舊時的客廳罷,我們在城中初見和將別時候的客廳。現在我還用著這客廳。這裡有新的賓客,新的饋贈,新的頌揚,新的鑽營,新的磕頭和打拱,新的打牌和猜拳,新的冷眼和噁心,新的失眠和吐血……。

「你前信說你教書很不如意。你願意也做顧問么?可以告訴我,我給你辦。其實是做門房也不妨,一樣地有新的賓客和新的饋贈,新的頌揚……。

「我這裡下大雪了。你那裡怎樣?現在已是深夜,吐了兩口血,使我清醒起來。記得你竟從秋天以來陸續給了我三封信,這是怎樣的可以驚異的事呵。我必須寄給你一點消息,你或者不至於倒抽一口冷氣罷。

「此後,我大約不再寫信的了,我這習慣是你早已知道的。何時回來呢?倘早,當能相見。——但我想,我們大概究竟不是一路的;那麼,請你忘記我罷。我從我的真心感謝你先前常替我籌劃生計。但是現在忘記我罷;我現在已經『好』了。

連殳。十二月十四日。」

這雖然並不使我「倒抽一口冷氣」,但草草一看之後,又細看了一遍,卻總有些不舒服,而同時可又夾雜些快意和高興;又想,他的生計總算已經不成問題,我的擔子也可以放下了,雖然在我這一面始終不過是無法可想。忽而又想寫一封信回答他,但又覺得沒有話說,於是這意思也立即消失了。

我的確漸漸地在忘卻他。在我的記憶中,他的面貌也不再時常出現。但得信之後不到十天,S城的學理七日報社忽然接續著郵寄他們的《學理七日報》來了。我是不大看這些東西的,不過既經寄到,也就隨手翻翻。這卻使我記起連殳來,因為裡面常有關於他的詩文,如《雪夜謁連殳先生》,《連殳顧問高齋雅集》等等;有一回,《學理閑譚》里還津津地敘述他先前所被傳為笑柄的事,稱作「逸聞」,言外大有「且夫非常之人,必能行非常之事」〔11〕的意思。

不知怎地雖然因此記起,但他的面貌卻總是逐漸模胡;然而又似乎和我日加密切起來,往往無端感到一種連自己也莫明其妙的不安和極輕微的震顫。幸而到了秋季,這《學理七日報》就不寄來了;山陽的《學理周刊》上卻又按期登起一篇長論文:《流言即事實論》。裡面還說,關於某君們的流言,已在公正士紳間盛傳了。這是專指幾個人的,有我在內;我只好極小心,照例連吸煙捲的煙也謹防飛散。小心是一種忙的苦痛,因此會百事俱廢,自然也無暇記得連殳。總之:我其實已經將他忘卻了。

但我也終於敷衍不到暑假,五月底,便離開了山陽。

IV

The teaching profession in Shanyang was no bed of roses. I taught for two months without receiving a cent of salary, until I had to cut down on cigarettes. But the school staff, even those earning only fifteen or sixteen dollars a month, were easily contented. They all had iron constitutions steeled by hardship, and, although lean and haggard, they worked from morning till night; while if interrupted at work by their superiors, they stood up respectfully. Thus they all practised plain living and high thinking. This reminded me, somehow, of Wei's parting words. He was then even more hard up, and often looked embarrassed, having apparently lost his former cynicism. When he heard that I was leaving, he came late at night to see me off, and, after hesitating for some rime, he stuttered:

"Would there be anything for me there? Even copying work, at twenty to thirty dollars a month, would do. I . . . ."

I was surprised. I had not thought he would consider anything so low, and did nor know how to answer.

"I . . . I have to live a little longer. . . ."

"I'll look out when I get there. I'll do my best."

This was what I had promised at the rime, and the words often rang in my ears later, as if Wei were still before me, stuttering: "I have to live a little longer." I tried to interest various people in his case, but to no avail. Since there were few vacancies, and many unemployed, these people always ended by apologizing for being unable to help, and I would write him an apologetic letter. By the end of the term, things had gone from bad to worse. The magazine Reason, edited by some of the local gentry, began to attack me. Naturally no names were mentioned, but it cleverly insinuated that I was stirring up trouble in the school, even my recommendation of Wei being interpreted as a manoeuvre to gather a clique about me.

So I had to keep quiet. Apart from attending class, I lay low in my room, sometimes when cigarette smoke escaped from my window, I even feared they might consider I was stirring up trouble. For Wei, naturally, I could do nothing. This state of affairs prevailed till midwinter.

It had been snowing all day, and the snow had not stopped by evening. Outside was so still, you could almost hear the sound of stillness. I closed my eyes and sat there in the dim lamplight doing nothing, imagining the snow-flakes falling, creating boundless drifts of snow. It would be nearly New Year at home too, and everybody would be busy. I saw myself a child again, making a snow man with a group of children on the level ground in the back yard. The eyes of the snow man, made of jet-black fragments of coal, suddenly turned into Wei's eyes.

"I have to live a little longer." The same voice again.

"What for?" I asked inadvertently, aware immediately of the ineptitude of my remark.

This reply woke me up. I sat up, lit a cigarette and opened the window, only to find the snow' falling even faster. I heard a knock at the door, and a moment later it opened to admit the servant, whose step I knew. He handed me a big envelope, more than six inches in length. The address was scrawled, but I saw Wei's name on it.

This was the first letter he had written me since I left S——. Knowing he was a bad correspondent, I had not wondered at his silence, only sometimes I had felt he should have given me some news of himself. The receipt of this letter was quite a surprise. I tore it open. The letter had been hastily scrawled, and said:

". . . Shen-fei,

"How should I address you? I am leaving a blank for you to fill in as you please. It will be all the same to me.

"I have received three letters from you altogether. I did nor reply for one simple reason: I had no money even to buy stamps.

"Perhaps you would like to know what has happened to me. To put it simply: I have failed. I thought I had failed before, but I was wrong then; now, however, I am really a failure. Formerly there was someone who wanted me to live a little longer, and I wished it too, but found it difficult. Now, there is no need, yet I must go on living. . . .

"Shall I live on?

"The one who wanted me to live a little longer could not live himself. He was trapped and killed by the enemy. Who killed him? No one knows.

"Changes take place so swiftly! During the last half year I have virtually been a beggar; it's true, I could be considered a beggar. However, I had my purpose: I was willing to beg for the cause, to go cold and hungry for it, to be lonely for it, to suffer hardship for it. But I did not want to destroy myself. So you see, the fact that one person wanted me to live on, proved extremely potent. Now there is no one, nor one. Ar the same time I feel I do nor deserve to live, nor, in my opinion, do some other people. Yet, I am conscious of wanting to live on to spite those who wish me dead; for at least there is no one left who wants me to live decently, and so no one will be hurt. I don't want to hurt such people. But now there is no one, not one. What a joy! Wonderful! I am now doing what I formerly detested and opposed. I am now giving up all I formerly believed in and upheld. I have really failed—but I have won.

"Do you think I am mad? Do you think I have become a hero or a great man? No, it is not that. It is very simple; I have become adviser to General Tu, hence I have eighty dollars salary a month.

". . .Shen-fei,.

"What will you think of me? You decide; it is all the same to me. . .

"Perhaps you still remember my former sitting-room, the one in which we had our first and last talks. I am still using it. There are new guests, new bribes, new flattery, new seeking for promotion, new kowtows and bows, new mahjong and drinking games, new haughtiness and disgust, new sleeplessness and vomiting of blood. . . .

"You said in your last letter that your teaching was nor going well. Would you like to be an adviser? Say the word, and I will arrange it for you. Actually, work in the gatehouse would be the same. There would be the same guests, bribes and flattery. . .

"It is snowing heavily here. How is it where you are? It is now midnight, and having just vomited some blood has sobered me. I recall that you have actually written three times in succession to me since autumn—amazing! I give you this news of myself, hoping you will not be shocked..

"I probably shall nor write again; you know my ways of old. When will you be back? If you come soon, we may meet again. Still, I suppose we have taken different roads; you had better forget me. I thank you from the bottom of my heart for trying to find work for me. Now please forget me; I am doing 'well.'.

Wei Lien-shu

December 14th.

Though this letter did not "shock" me, when, after a hasty perusal, I read it carefully again, I felt both uneasy and relieved. At least his livelihood was secure, and I need not worry about that any more. At any rate, I could do nothing here. I thought of writing to him, but felt there was nothing to say.

In fact, I gradually forgot him. His face no longer sprang so often to my mind's eye. However, less than ten days after hearing from him, the office of the S—— Weekly started sending me its paper. I did not read such papers as a rule, but since it was sent to me I glanced at some of the contents. This reminded me of Wei, for the paper frequently carried poems and essays about him, such as "Calling on scholar Wei at night during a snowstorm," "A poetic gathering at the scholarly abode of Adviser Wei," and so forth. Once, indeed, under the heading "Table Talk," they retailed with gusto certain stories which had previously been considered material for ridicule, but which had now become "Tales of an Eccentric Genius." Only an exceptional man, it was implied, could have done such unusual things.

Although this recalled him to me, my impression of him grew fainter. Yet all the time he seemed to gain a closer hold on me, which often filled me with an inexplicable sense of uneasiness and a shadowy apprehension. However, by autumn the newspaper stopped coming, while the Shanyang magazine began to publish the first instalment of a long essay called "The element of truth in rumours," which asserted that rumours about certain gentlemen had reached the ears of the mighty. My name was among those attacked. I had to be very careful then. I had to take care that my cigarette smoke did not get in other people's way. All these precautions took so much time I could attend to nothing else, and naturally had no leisure to think of Wei. I actually forgot him.

I could nor hold my job till summer. By the end of May I had to leave Shanyang.

五

從山陽到歷城,又到太谷,一總轉了大半年,終於尋不出什麼事情做,我便又決計回S城去了。到時是春初的下午,天氣欲雨不雨,一切都罩在灰色中;舊寓里還有空房,仍然住下。在道上,就想起連殳的了,到后,便決定晚飯後去看他。我提著兩包聞喜名產的煮餅,走了許多潮濕的路,讓道給許多攔路高卧的狗,這才總算到了連殳的門前。裡面彷彿特別明亮似的。我想,一做顧問,連寓里也格外光亮起來了,不覺在暗中一笑。但仰面一看,門旁卻白白的,分明帖著一張斜角紙〔12〕。我又想,大良們的祖母死了罷;同時也跨進門,一直向裡面走。

微光所照的院子里,放著一具棺材,旁邊站一個穿軍衣的兵或是馬弁,還有一個和他談話的,看時卻是大良的祖母;另外還閑站著幾個短衣的粗人。我的心即刻跳起來了。她也轉過臉來凝視我。

「阿呀!您回來了?何不早幾天……。」她忽而大叫起來。

「誰……誰沒有了?」我其實是已經大概知道的了,但還是問。

「魏大人,前天沒有的。」

我四顧,客廳里暗沉沉的,大約只有一盞燈;正屋裡卻掛著白的孝幃,幾個孩子聚在屋外,就是大良二良們。

「他停在那裡,」大良的祖母走向前,指著說,「魏大人恭喜之後,我把正屋也租給他了;他現在就停在那裡。」

孝幃上沒有別的,前面是一張條桌,一張方桌;方桌上擺著十來碗飯菜。我剛跨進門,當面忽然現出兩個穿白長衫的來攔住了,瞪了死魚似的眼睛,從中發出驚疑的光來,釘住了我的臉。我慌忙說明我和連殳的關係,大良的祖母也來從旁證實,他們的手和眼光這才逐漸弛緩下去,默許我近前去鞠躬。

我一鞠躬,地下忽然有人嗚嗚的哭起來了,定神看時,一個十多歲的孩子伏在草荐上,也是白衣服,頭髮剪得很光的頭上還絡著一大綹薴麻絲〔13〕。

我和他們寒暄后,知道一個是連殳的從堂兄弟,要算最親的了;一個是遠房侄子。我請求看一看故人,他們卻竭力攔阻,說是「不敢當」的。然而終於被我說服了,將孝幃揭起。

這回我會見了死的連殳。但是奇怪!他雖然穿一套皺的短衫褲,大襟上還有血跡,臉上也瘦削得不堪,然而面目卻還是先前那樣的面目,寧靜地閉著嘴,合著眼,睡著似的,幾乎要使我伸手到他鼻子前面,去試探他可是其實還在呼吸著。

一切是死一般靜,死的人和活的人。我退開了,他的從堂兄弟卻又來周旋,說「舍弟」正在年富力強,前程無限的時候,竟遽爾「作古」了,這不但是「衰宗」不幸,也太使朋友傷心。言外頗有替連殳道歉之意;這樣地能說,在山鄉中人是少有的。但此後也就沉默了,一切是死一般靜,死的人和活的人。

我覺得很無聊,怎樣的悲哀倒沒有,便退到院子里,和大良們的祖母閑談起來。知道入殮的時候是臨近了,只待壽衣送到;釘棺材釘時,「子午卯酉」四生肖是必須躲避的。她談得高興了,說話滔滔地泉流似的湧出,說到他的病狀,說到他生時的情景,也帶些關於他的批評。

「你可知道魏大人自從交運之後,人就和先前兩樣了,臉也抬高起來,氣昂昂的。對人也不再先前那麼迂。你知道,他先前不是像一個啞子,見我是叫老太太的么?後來就叫『老傢伙』。唉唉,真是有趣。人送他仙居術〔14〕,他自己是不吃的,就摔在院子里,——就是這地方,——叫道,『老傢伙,你吃去罷。』他交運之後,人來人往,我把正屋也讓給他住了,自己便搬在這廂房裡。他也真是一走紅運,就與眾不同,我們就常常這樣說笑。要是你早來一個月,還趕得上看這裡的熱鬧,三日兩頭的猜拳行令,說的說,笑的笑,唱的唱,做詩的做詩,打牌的打牌……。

「他先前怕孩子們比孩子們見老子還怕,總是低聲下氣的。近來可也兩樣了,能說能鬧,我們的大良們也很喜歡和他玩,一有空,便都到他的屋裡去。他也用種種方法逗著玩;要他買東西,他就要孩子裝一聲狗叫,或者磕一個響頭。哈哈,真是過得熱鬧。前兩月二良要他買鞋,還磕了三個響頭哩,哪,現在還穿著,沒有破呢。」

一個穿白長衫的人出來了,她就住了口。我打聽連殳的病症,她卻不大清楚,只說大約是早已瘦了下去的罷,可是誰也沒理會,因為他總是高高興興的。到一個多月前,這才聽到他吐過幾回血,但似乎也沒有看醫生;後來躺倒了;死去的前三天,就啞了喉嚨,說不出一句話。十三大人從寒石山路遠迢迢地上城來,問他可有存款,他一聲也不響。十三大人疑心他裝出來的,也有人說有些生癆病死的人是要說不出話來的,誰知道呢……。

「可是魏大人的脾氣也太古怪,」她忽然低聲說,「他就不肯積蓄一點,水似的化錢。十三大人還疑心我們得了什麼好處。有什麼屁好處呢?他就冤里冤枉胡裡胡塗地化掉了。譬如買東西,今天買進,明天又賣出,弄破,真不知道是怎麼一回事。待到死了下來,什麼也沒有,都糟掉了。要不然,今天也不至於這樣地冷靜……。

「他就是胡鬧,不想辦一點正經事。我是想到過的,也勸過他。這麼年紀了,應該成家;照現在的樣子,結一門親很容易;如果沒有門當戶對的,先買幾個姨太太也可以:人是總應該像個樣子的。可是他一聽到就笑起來,說道,『老傢伙,你還是總替別人惦記著這等事么?』你看,他近來就浮而不實,不把人的好話當好話聽。要是早聽了我的話,現在何至於獨自冷清清地在陰間摸索,至少,也可以聽到幾聲親人的哭聲……。」

一個店伙背了衣服來了。三個親人便檢出裡衣,走進幃後去。不多久,孝幃揭起了,裡衣已經換好,接著是加外衣。

這很出我意外。一條土黃的軍褲穿上了,嵌著很寬的紅條,其次穿上去的是軍衣,金閃閃的肩章,也不知道是什麼品級,那裡來的品級。到入棺,是連殳很不妥帖地躺著,腳邊放一雙黃皮鞋,腰邊放一柄紙糊的指揮刀,骨瘦如柴的灰黑的臉旁,是一頂金邊的軍帽。

三個親人扶著棺沿哭了一場,止哭拭淚;頭上絡麻線的孩子退出去了,三良也避去,大約都是屬「子午卯酉」之一的。

粗人打起棺蓋來,我走近去最後看一看永別的連殳。

他在不妥帖的衣冠中,安靜地躺著,合了眼,閉著嘴,口角間彷彿含著冰冷的微笑,冷笑著這可笑的死屍。

敲釘的聲音一響,哭聲也同時迸出來。這哭聲使我不能聽完,只好退到院子里;順腳一走,不覺出了大門了。潮濕的路極其分明,仰看太空,濃雲已經散去,掛著一輪圓月,散出冷靜的光輝。

我快步走著,彷彿要從一種沉重的東西中衝出,但是不能夠。耳朵中有什麼掙扎著,久之,久之,終於掙扎出來了,隱約像是長嗥,像一匹受傷的狼,當深夜在曠野中嗥叫,慘傷里夾雜著憤怒和悲哀。

我的心地就輕鬆起來,坦然地在潮濕的石路上走,月光底下。

一九二五年十月十七日畢。

V

I wandered between Shanyang, Licheng and Taiku for more than half a year, but could find no work, so I decided to go back to S——. I arrived one afternoon in early spring. It was a cloudy day with everything wrapped in mist. Since there were vacant rooms in my old hostel, I stayed there. On the road I started to think of Wei, and after my arrival I made up my mind to call on him after dinner. Taking two packages of the well-known Wenhsi cakes, I threaded my way through several damp streets, stepping cautiously past many sleeping dogs, until I reached his door. It seemed very bright inside. I thought even his rooms were better lit since he had become an adviser, and smiled to myself. However, when I looked up, I saw a strip of white paper3 stuck on the door. It occurred to me, as I stepped inside, that the children's grandmother might be dead; but I went straight in.

In the dimly lit courtyard there was a coffin, by which some soldier or orderly in uniform was standing, talking to the children's grandmother. A few workers in short coats were loitering there too. My heart began to beat faster. Just then she turned to look at me.

"Ah, you're back?" she exclaimed. "Why didn't you come earlier?"

"Who . . . who has passed away?" Actually by now I knew, yet I asked all the same.

"Adviser Wei died the day before yesterday."

I looked around. The sitting-room was dimly lit, probably by one lamp only; the front room, however, was decked with white funeral curtains, and the woman's grandchildren had gathered outside that room.

"His body is there," she said, coming forward and pointing to the front room. "After Mr. Wei was promoted, I let him my front room too; that is where he is now."

There was no writing on the funeral curtain. In front stood a long table, then a square table, spread with some dozen dishes. As I went in, two men in long white gowns suddenly appeared to bar the way, their eyes, like those of a dead fish, fixed in surprise and mistrust on my face. I hastily explained my relationship with Wei, and the landlady came up to confirm my statement. Then their hands and eyes dropped, and they allowed me to go forward to bow to the dead.

As I bowed, a wail sounded beside me from the floor. Looking down I saw a child of about ten, also dressed in white, kneeling on a mat. His hair had been cut short, and had some hemp attached to it.

Later I found out one of these men was Wei's cousin, his nearest in kin, while the other was a distant nephew. I asked to be allowed to see Wei, but they tried their best to dissuade me, saying I was too "polite." Finally they gave in, and lifted the curtain.

This time I saw Wei in death. But, strangely enough, though he was wearing a crumpled shirt, stained in front with blood, and his face was very lean, his expression was unchanged. He was sleeping so placidly, with closed mouth and eyes, that I was tempted to put my finger before his nostrils to see if he were still breathing.

Everything was deathly still, both the living and the dead. As I withdrew, his cousin accosted me to state that Wei's untimely death, just when he was in the prime of life and had a great future before him, was not only a calamity for his humble family but a cause of sorrow for his friends. He seemed to be apologizing for Wei for dying. Such eloquence is rare among villagers. However, after that he fell silent again and everything was deathly still, both the living and the dead.

Feeling cheerless, but by no means sad, I withdrew to the courtyard to chat with the old woman. She told me the funeral would soon take place. They were waiting for the shroud, she said, and when the coffin was nailed down, people born under certain stars should nor be near. She rattled on, her words pouring out like a flood. She spoke of Wei's illness, incidents during his life, and even voiced certain criticisms.

"You know, after Mr. Wei came into luck, he was a different man. He held his head high and looked very haughty. He stopped treating people in his old formal way. Did you know, he used to act like an idiot, and call me madam? Later on, she chuckled, "he called me 'old bitch'; it was too funny for words. When people sent him rare herbs like atractylis, instead of eating them himself, he would throw them into the courtyard, just here, and call out, 'You take this, old bitch!' After he came into luck, he had scores of visitors; so I vacated my front room for him, and moved into a side one. As we have always said jokingly, he became a different man after his good luck. If you had come one month earlier, you could have seen all the fun here: drinking games practically every day, talking, laughing, singing, poetry writing and mah-jong games. . . .

"He used to be more afraid of children than they are of their own father, practically grovelling to them. But recently that changed too, and he was a good one for jokes. My grandchildren liked to play with him, and would go to his rooms whenever they could. He would think up all sorts of practical jokes. For instance, when they wanted him to buy things for them, he would make them bark like dogs or make a thumping kowtow. Ah, that was fun. Two months ago, my second grandchild asked Mr. Wei to buy him a pair of shoes, and had to make three thumping kowtows. He's still wearing them; they aren't worn out yet."

When one of the men in white came out, she stopped talking. I asked about Wei's illness, but there was little she could tell me. She knew only that he had been losing weight for a long time, but they had thought nothing of it because he always looked so cheerful. About a month before, they heard he had been coughing blood, but it seemed he had not seen a doctor. Then he had to stay in bed, and three days before he died he seemed to have lost the power of speech. His cousin had come all the way from the village to ask him if he had any savings, but he said not a word. His cousin thought he was shamming, but some people say those dying of consumption do lose the power of speech. . . .

"But Mr. Wei was a queer man," she suddenly whispered. "He never saved money, always spent it like water. His cousin still suspects we got something out of him. Heaven knows, we got nothing. He just spent it in his haphazard way. Buying something today, selling it tomorrow, or breaking it up—God knows what happened. When he died there was nothing left, all spent! Otherwise it would not be so dismal today. . . .

"He just fooled about, not wanting to do the proper thing. At his age, he should have got married; I had thought of that, and spoken to him. It would have been easy for him then. And if no suitable family could be found, at least he could have bought a few concubines to go on with. People should keep up appearances. But he would laugh whenever I brought it up. 'Old bitch, you are always worrying about such things for other people,' he would say. He was never serious, you see; he wouldn't listen to good advice. If he had listened to me, he wouldn't be wandering lonely in the nether world now; at least his dear ones would be wailing. . . . ."

A shop assistant arrived, bringing some clothes with him. The three relatives of the dead picked out the underwear, then disappeared behind the curtain. Soon, the curtain was lifted; the new underwear had been put on the corpse, and they proceeded to put on his outer garments. I was surprised to see them dress him in a pair of khaki military trousers with broad red stripes, and a tunic with glittering epaulettes. I did not know what rank these indicated, or how he had acquired it. The body was placed in the coffin. Wei lay there awkwardly, a pair of brown leather shoes beside his feet, a paper sword at his waist, and beside his lean and ashen face a military cap with a gilt band.

The three relatives wailed beside the coffin, then stopped and wiped away their tears. The boy with hemp attached to his hair withdrew, as did the old woman's third grandchild—no doubt they were born under the wrong stars.

As the labourers lifted the coffin lid, I stepped forward to see Wei for the last time.

In his awkward costume he lay placidly, with closed mouth and eyes. There seemed to be an ironical smile on his lips, mocking the ridiculous corpse.

When they began to hammer in the nails, the wailing started afresh. I could not stand it very long, so I withdrew to the courtyard; then, somehow, I was out of the gate. The damp road glistened, and I looked up at the sky where the cloud banks had scattered and a full moon hung, shedding a cold light.

I walked with quickened steps, as if eager to break through some heavy barrier, but finding it impossible. Something struggled in my ears, and, after a long, long time, burst out. It was like a long howl, the howl of a wounded wolf crying in the wilderness in the depth of night, anger and sorrow mingled in its agony.

Then my heart felt lighter, and I paced calmly on under the moon along the damp cobbled road.

〔1〕本篇在收入本書前未在報刊上發表過。

〔2〕「承重孫」按封建宗法制度,長子先亡,由嫡長孫代替亡父充當祖父母喪禮的主持人,稱承重孫。

〔3〕法事原指佛教徒念經、供佛一類活動。這裡指和尚、道士超度亡魂的迷信儀式,也叫「做功德」。

〔4〕《沉淪》小說集,郁達夫著,內收中篇小說《沉淪》和短篇小說《南遷》、《銀灰色的死》,一九二一年十月上海泰東圖書局出版。這些作品以「不幸的青年」或「零餘者」為主人公,反映當時一部分小資產階級知識分子在帝國主義、封建勢力壓抑下的憂鬱、苦悶和自暴自棄的病態心理,帶有頹廢的傾向。

〔5〕吃素談禪談禪,指談論佛教教義。當時軍閥官僚在失勢后,往往發表下野「宣言」或「通電」,宣稱出洋遊歷或隱居山林、吃齋念佛,從此不問國事等,實則窺測方向,伺機再起。

〔6〕《史記索隱》唐代司馬貞註釋《史記》的書,共三十卷。汲古閣,是明末藏書家毛晉的藏書室。《史記索隱》是毛晉重刻的宋版書之一。

〔7〕「一日不見,如隔三秋」語出《詩經·王風·采葛》:「一日不見,如三秋兮。」

〔8〕獨頭繭紹興方言稱孤獨的人為獨頭。蠶吐絲作繭,將自己孤獨地裹在裡面,所以這裡用「獨頭繭」比喻自甘孤獨的人。

〔9〕「衣食足而知禮節」語出《管子·牧民》:「倉廩實則知禮節,衣食足則知榮辱。」

〔10〕挑剔學潮一九二五年五月,作者和北京女子師範大學其他六位教授發表了支持該校學生反對反動的學校當局的宣言,陳西瀅於同月《現代評論》第一卷第二十五期發表的《閑話》中,攻擊作者等是「暗中挑剔風潮」。作者在這裡借用此語,含有諷刺陳西瀅文句不通的意味。

〔11〕「且夫非常之人,必能行非常之事」語出《史記·司馬相如列傳》:「蓋世必有非常之人,然後有非常之事。」

〔12〕斜角紙我國舊時民間習俗,人死後在大門旁斜貼一張白紙,紙上寫明死者的性別和年齡,入殮時需要避開的是哪些生肖的人,以及「殃」和「煞」的種類、日期,使別人知道避忌。(這就是所謂「殃榜」。據清代范寅《越諺》:煞神,「人首雞身」,「人死必如期至,犯之輒死」。)

〔13〕薴麻絲指「麻冠」(用薴麻編成)。舊時習俗,死者的兒子或承重孫在守靈和送殯時戴用,作為「重孝」的標誌。

〔14〕仙居術浙江省仙居縣所產的藥用植物白朮。

1. A contemporary of Lu Hsun's, who wrote ahout repressed young men.

2. By Ssuma Chen of the Tang dynasty (618-907).

3. White is the mourning colour in China. White paper on the door indicated that there had heen a death in the house.

"Not always," I answered casually.

"Always. Children have none of the faults of grown-ups. If they turn out badly later, as you contend, it is because they have been moulded by their environment. Originally they are nor bad, but innocent. . . . I think China's only hope lies in this."

"I don't agree. Without the root of evil, how could they bear evil fruit in later life? Take a seed, for example. It is because it contains the embryo leaves, flowers and fruits, that later it grows into these things. There must be a cause. . . ." Since my unemployment, just like those great officials who resigned from office and took up Buddhism, I had been reading the Buddhist sutras. I did not understand Buddhist philosophy though, and was just talking at random.

However, Wei was annoyed. He gave me a look, then said no more. I could nor tell whether he had no more to say, or whether he felt it not worth arguing with me. But he looked cold again, as he had nor done for a long time, and smoked two cigarettes one after the other in silence. By the time he reached for the third cigarette, I beat a retreat.

Our estrangement lasted three months. Then, owing in part to forgetfulness, in part to the fact that he fell out with those "innocent" children, he came to consider my slighting remarks on children as excusable. Or so I surmised. This happened in my house after drinking one day, when, with a rather melancholy look, he cocked his head and said:

"Come to think of it, it's really curious. On my way here I met a small child with a reed in his hand, which he pointed at me, shouting, 'Kill!' He was just a toddler. . . ."

"He must have been moulded by his environment."

As soon as I had said this, I wanted to take it back. However, he did not seem to care, just went on drinking heavily, smoking furiously in between.

"I meant to ask you," I said, trying to change the subject. "You don't usually call on people, what made you come out today? I've known you for more than a year, yet this is the first time you've been here."

"I was just going to tell you: don't call on me for the time being. There are a father and son in my place who are perfect pests. They are scarcely human!"

"Father and son? Who are they?" I was surprised.

"My cousin and his son. Well, the son resembles the father."

"I suppose they came to town to see you and have a good time?"

"No. They came to talk me into adopting the boy."

"What, to adopt the boy?" I exclaimed in amazement. "But you are not married."

"They know I won't marry. But that's nothing to them. Actually they want to inherit that tumbledown house of mine in the village. I have no other property, you know; as soon as I get money I spend it. I've only that house. Their purpose in life is to drive out the old maidservant who is living in the place for the time being."

The cynicism of his remark took me aback. However I tried to soothe him, by saying:

"I don't think your relatives can be so bad. They are only rather old-fashioned. For instance, that year when you cried bitterly, they came forward eagerly to plead with you.

"When I was a child and my father died, I cried bitterly because they wanted to take the house from me and make me put my mark on the document. They came forward eagerly then to plead with me. . . ." He looked up, as if searching the air for that bygone scene.

"The crux of the matter is—you have no children. Why don't you get married?" I had found a way to change the subject, and this was something I had been wanting to ask for a long time. It seemed an excellent opportunity.

He looked at me in surprise, then dropped his gaze to his knees, and started smoking. I received no answer to my question.

三

但是,雖在這一種百無聊賴的境地中,也還不給連殳安住。漸漸地,小報上有匿名人來攻擊他,學界上也常有關於他的流言,可是這已經並非先前似的單是話柄,大概是於他有損的了。我知道這是他近來喜歡發表文章的結果,倒也並不介意。S城人最不願意有人發些沒有顧忌的議論,一有,一定要暗暗地來叮他,這是向來如此的,連殳自己也知道。但到春天,忽然聽說他已被校長辭退了。這卻使我覺得有些兀突;其實,這也是向來如此的,不過因為我希望著自己認識的人能夠倖免,所以就以為兀突罷了,S城人倒並非這一回特別惡。

其時我正忙著自己的生計,一面又在接洽本年秋天到山陽去當教員的事,竟沒有工夫去訪問他。待到有些餘暇的時候,離他被辭退那時大約快有三個月了,可是還沒有發生訪問連殳的意思。有一天,我路過大街,偶然在舊書攤前停留,卻不禁使我覺到震悚,因為在那裡陳列著的一部汲古閣初印本《史記索隱》〔6〕,正是連殳的書。他喜歡書,但不是藏書家,這種本子,在他是算作貴重的善本,非萬不得已,不肯輕易變賣的。難道他失業剛才兩三月,就一貧至此么?雖然他向來一有錢即隨手散去,沒有什麼貯蓄。於是我便決意訪問連殳去,順便在街上買了一瓶燒酒,兩包花生米,兩個熏魚頭。

他的房門關閉著,叫了兩聲,不見答應。我疑心他睡著了,更加大聲地叫,並且伸手拍著房門。

「出去了罷!」大良們的祖母,那三角眼的胖女人,從對面的窗口探出她花白的頭來了,也大聲說,不耐煩似的。

「那裡去了呢?」我問。

「那裡去了?誰知道呢?——他能到那裡去呢,你等著就是,一會兒總會回來的。」

我便推開門走進他的客廳去。真是「一日不見,如隔三秋」〔7〕,滿眼是凄涼和空空洞洞,不但器具所余無幾了,連書籍也只剩了在S城決沒有人會要的幾本洋裝書。屋中間的圓桌還在,先前曾經常常圍繞著憂鬱慷慨的青年,懷才不遇的奇士和腌臟吵鬧的孩子們的,現在卻見得很閑靜,只在面上蒙著一層薄薄的灰塵。我就在桌上放了酒瓶和紙包,拖過一把椅子來,靠桌旁對著房門坐下。

的確不過是「一會兒」,房門一開,一個人悄悄地陰影似的進來了,正是連殳。也許是傍晚之故罷,看去彷彿比先前黑,但神情卻還是那樣。

「阿!你在這裡?來得多久了?」他似乎有些喜歡。

「並沒有多久。」我說,「你到那裡去了?」

「並沒有到那裡去,不過隨便走走。」

他也拖過椅子來,在桌旁坐下;我們便開始喝燒酒,一面談些關於他的失業的事。但他卻不願意多談這些;他以為這是意料中的事,也是自己時常遇到的事,無足怪,而且無可談的。他照例只是一意喝燒酒,並且依然發些關於社會和歷史的議論。不知怎地我此時看見空空的書架,也記起汲古閣初印本的《史記索隱》,忽而感到一種淡漠的孤寂和悲哀。

「你的客廳這麼荒涼……。近來客人不多了么?」

「沒有了。他們以為我心境不佳,來也無意味。心境不佳,實在是可以給人們不舒服的。冬天的公園,就沒有人去……。」

他連喝兩口酒,默默地想著,突然,仰起臉來看著我問道,「你在圖謀的職業也還是毫無把握罷?……」

我雖然明知他已經有些酒意,但也不禁憤然,正想發話,只見他側耳一聽,便抓起一把花生米,出去了。門外是大良們笑嚷的聲音。

但他一出去,孩子們的聲音便寂然,而且似乎都走了。他還追上去,說些話,卻不聽得有回答。他也就陰影似的悄悄地回來,仍將一把花生米放在紙包里。

「連我的東西也不要吃了。」他低聲,嘲笑似的說。

「連殳,」我很覺得悲涼,卻強裝著微笑,說,「我以為你太自尋苦惱了。你看得人間太壞……。」

他冷冷的笑了一笑。

「我的話還沒有完哩。你對於我們,偶而來訪問你的我們,也以為因為閑著無事,所以來你這裡,將你當作消遣的資料的罷?」

「並不。但有時也這樣想。或者尋些談資。」

「那你可錯誤了。人們其實並不這樣。你實在親手造了獨頭繭〔8〕,將自己裹在裡面了。你應該將世間看得光明些。」我嘆惜著說。

「也許如此罷。但是,你說:那絲是怎麼來的?——自然,世上也盡有這樣的人,譬如,我的祖母就是。我雖然沒有分得她的血液,卻也許會繼承她的運命。然而這也沒有什麼要緊,我早已豫先一起哭過了……。」

我即刻記起他祖母大殮時候的情景來,如在眼前一樣。

「我總不解你那時的大哭……。」於是鶻突地問了。

「我的祖母入殮的時候罷?是的,你不解的。」他一面點燈,一面冷靜地說,「你的和我交往,我想,還正因為那時的哭哩。你不知道,這祖母,是我父親的繼母;他的生母,他三歲時候就死去了。」他想著,默默地喝酒,吃完了一個熏魚頭。

「那些往事,我原是不知道的。只是我從小時候就覺得不可解。那時我的父親還在,家景也還好,正月間一定要懸掛祖像,盛大地供養起來。看著這許多盛裝的畫像,在我那時似乎是不可多得的眼福。但那時,抱著我的一個女工總指了一幅像說:『這是你自己的祖母。拜拜罷,保佑你生龍活虎似的大得快。』我真不懂得我明明有著一個祖母,怎麼又會有什麼『自己的祖母』來。可是我愛這『自己的祖母』,她不比家裡的祖母一般老;她年青,好看,穿著描金的紅衣服,戴著珠冠,和我母親的像差不多。我看她時,她的眼睛也注視我,而且口角上漸漸增多了笑影:我知道她一定也是極其愛我的。

「然而我也愛那家裡的,終日坐在窗下慢慢地做針線的祖母。雖然無論我怎樣高興地在她面前玩笑,叫她,也不能引她歡笑,常使我覺得冷冷地,和別人的祖母們有些不同。但我還愛她。可是到後來,我逐漸疏遠她了;這也並非因為年紀大了,已經知道她不是我父親的生母的緣故,倒是看久了終日終年的做針線,機器似的,自然免不了要發煩。但她卻還是先前一樣,做針線;管理我,也愛護我,雖然少見笑容,卻也不加呵斥。直到我父親去世,還是這樣;後來呢,我們幾乎全靠她做針線過活了,自然更這樣,直到我進學堂……。」

燈火銷沉下去了,煤油已經將涸,他便站起,從書架下摸出一個小小的洋鐵壺來添煤油。

「只這一月里,煤油已經漲價兩次了……。」他旋好了燈頭,慢慢地說。「生活要日見其困難起來。——她後來還是這樣,直到我畢業,有了事做,生活比先前安定些;恐怕還直到她生病,實在打熬不住了,只得躺下的時候罷……。

「她的晚年,據我想,是總算不很辛苦的,享壽也不小了,正無須我來下淚。況且哭的人不是多著么?連先前竭力欺凌她的人們也哭,至少是臉上很慘然。哈哈!……可是我那時不知怎地,將她的一生縮在眼前了,親手造成孤獨,又放在嘴裡去咀嚼的人的一生。而且覺得這樣的人還很多哩。這些人們,就使我要痛哭,但大半也還是因為我那時太過於感情用事……。

「你現在對於我的意見,就是我先前對於她的意見。然而我的那時的意見,其實也不對的。便是我自己,從略知世事起,就的確逐漸和她疏遠起來了……。」

他沉默了,指間夾著煙捲,低了頭,想著。燈火在微微地發抖。

「呵,人要使死後沒有一個人為他哭,是不容易的事呵。」

他自言自語似的說;略略一停,便仰起臉來向我道,「想來你也無法可想。我也還得趕緊尋點事情做……。」

「你再沒有可托的朋友了么?」我這時正是無法可想,連自己。

「那倒大概還有幾個的,可是他們的境遇都和我差不多……。」

我辭別連殳出門的時候,圓月已經升在中天了,是極靜的夜。

III

Yet he was not allowed to enjoy even this inane existence in peace. Gradually anonymous attacks appeared in the less reputable papers, and rumours concerning him were spread in the schools. This was not the simple gossip of the old days, but deliberately damaging. I knew this was the outcome of articles he had taken to writing for magazines, so I paid no attention. The citizens of S—— disliked nothing more than fearless argument, and anyone guilty of it indubitably became the object of secret attacks. This was the rule, and Wei knew it too. However, in spring, when I heard he had been asked by the school authorities to resign, I confessed it surprised me. Of course, this was only to be expected, and it surprised me simply because I had hoped my friend would escape. The citizens of S—— were not proving more vicious than usual.

I was occupied then with my own problems, negotiating to go to a school in Shanyang that autumn, so I had no time to call on him. Some three months passed before I was at leisure, and even then it had not occurred to me to visit him. One day, passing the main street, I happened to pause before a secondhand bookstall, where I was startled to see an early edition of the Commentaries on Ssuma Chien's "Historical Records"2 from Wei's collection on display. He was no connoisseur, but he loved books, and I knew he prized this particular one. He must be very hard pressed to have sold it. It seemed scarcely possible he could have become so poor only two or three months after losing his job; yet he spent money as soon as he had it, and had never saved. I decided to call on him. On the same street I bought a bottle of liquor, two packages of peanuts and two smoked fish-heads.

His door was closed. I called out twice, but there was no reply. Thinking he was asleep, I called louder, at the same time hammering on the door.

"He's probably out." The children's grandmother, a fat woman with small eyes, thrust her grey head our from the opposite window, and spoke impatiently.

"Where has he gone?" I asked.

"Where? Who knows—where could he go? You can wait, he will be back soon."

I pushed open the door and went into his sitting-room. It was greatly changed, looking desolate in its emptiness. There was little furniture left, while all that remained of his library were those foreign books which could not be sold. The middle of the room was still occupied by the table around which those woeful and gallant young men, unrecognized geniuses, and dirty, noisy children had formerly gathered. Now it all seemed very quiet, and there was a thin layer of dust on the table. I put the bottle and packages down, pulled over a chair, and sat down by the table facing the door.

Very soon, sure enough, the door opened, and someone stepped in as silently as a shadow. It was Wei. It might have been the twilight that made his face look dark; but his expression was unchanged.

"Ah, it's you? How long have you been here?" He seemed pleased.

"Not very long," I said. "Where have you been?"

"Nowhere in particular. Just taking a stroll."

He pulled up a chair too and sat by the table. We started drinking, and spoke of his losing his job. However, he did not care to talk much about it, considering it only to be expected. He had come across many similar cases. It was not strange at all, and nor worth discussing. As usual, he drank heavily, and discoursed on society and the study of history. Something made me glance at the empty bookshelves, and, remembering the Commentaries on Ssuma Chien's "Historical Records", I was conscious of a slight loneliness and sadness.

"Your sitting-room has a deserted look

Have you had fewer visitors recently?"

"None at all. They don't find it much fun when I'm not in a good mood. A bad mood certainly makes people uncomfortable Just as no one goes to the park in winter. . . ."

He took two sips of liquor in succession, then fell silent. Suddenly, looking up, he asked, "I suppose you have had no luck either in finding work?"

Although I knew he was only venting his feelings as a result of drinking, I felt indignant at the way people treated him. Just as I was about to say something, he pricked up his ears, then, scooping up some peanuts, went our. Outside, I could hear the laughter and shouts of the children.

But as soon as he went out, the children became quiet. It sounded as if they had left. He went after them, and said something, but I could hear no reply. Then, as silent as a shadow, he came back and put the handful of peanuts back in the package.

"They don't even want to eat anything I give them," he said sarcastically, in a low voice.

"Old Wei," I said, forcing a smile, although I was sick at heart, "I think you are tormenting yourself unnecessarily. Why think so poorly of your fellow men?"

He only smiled cynically.

"I haven't finished yet. I suppose you consider people like me, who come here occasionally, do so in order to kill time or amuse themselves at your expense?"

"No, I don't. Well, sometimes I do. Perhaps they come to find something to talk about."

"Then you are wrong. People are not like that. You are really wrapping yourself up in a cocoon. You should take a more cheerful view." I sighed.

"Maybe. But tell me, where does the thread for the cocoon come from? Of course, there are plenty of people like that; take my grandmother, for example. Although I have none of her blood in my veins, I may inherit her fate. But that doesn't matter, I have already bewailed my fate together with hers. . . ."

Then I remembered what had happened at his grandmother's funeral. I could almost see it before my eyes.

"I still don't understand why you cried so bitterly," I said bluntly.

"You mean at my grandmother's funeral? No, you wouldn't." He lit the lamp. "I suppose it was because of that that we became friends," he said quietly. "You know, this grandmother was my grandfather's second wife. My father's own mother died when he was three." Growing thoughtful, he drank silently, and finished a smoked fish-head.

"I didn't know it to begin with. Only, from my childhood I was puzzled. Ar that time my father was still alive, and our family was well off. During the lunar New Year we would hang up the ancestral images and hold a grand sacrifice. It was one of my rare pleasures to look at those splendidly dressed images. At that time a maidservant would always carry me to an image, and point at it, saying: 'This is your own grandmother. Bow to her so that she will protect you and make you grow up strong and healthy.' I could not understand how I came to have another grandmother, in addition to the one beside me. But I liked this grandmother who was 'my own.' She was not as old as the granny at home. Young and beautiful, wearing a red costume with golden embroidery and a headdress decked with pearls, she resembled my mother. When I looked at her, her eyes seemed to gaze down on me, and a faint smile appeared on her lips. I knew she was very fond of me too.

"But I liked the granny at home too, who sat all day under the window slowly plying her needle. However, no matter how merrily I laughed and played in front of her, or called to her, I could not make her laugh; and that made me feel she was cold, unlike other children's grandmothers. Still, I liked her. Later on, though, I gradually cooled towards her, nor because I grew older and learned she was not my own grandmother, but rather because I was exasperated by the way she kept on sewing mechanically, day in, day our. She was unchanged, however. She sewed, looked after me, loved and protected me as before; and though she seldom smiled, she never scolded me. It was the same after my father died. Later on, we lived almost entirely on her sewing, so it was still the same, until I went to school. . . ."

The light flickered as the paraffin gave out, and he stood up to refill the lamp from a small tin kettle under the bookcase.

"The price of paraffin has gone up twice this month," he said slowly, after turning up the wick. "Life becomes harder every day. She remained the same until I graduated from school and had a job, when our life became more secure. She didn't change, I suppose, until she was sick, couldn't carry on, and had to take to her bed. . . .

"Since her later days, I think, were not too unhappy on the whole, and she lived to a great age, I need not have mourned. Besides, weren't there a lot of others there eager to wail? Even those who had tried their hardest to rob her, wailed, or appeared bowed down with grief." He laughed. "However, at that moment her whole life rose to my mind—the life of one who created loneliness for herself and tasted its bitterness. I felt there were many people like that. I wanted to weep for them; but perhaps it was largely because I was too sentimental. . . .

"Your present advice to me is what I felt with regard to her. But actually my ideas at that time were wrong. As for myself, since I grew up my feelings for her cooled. . . ."

He paused, with a cigarette between his fingers; and bending his head lost himself in thought. The lamplight flickered.

"Well, it is hard to live so that no one will mourn for your death," he said, as if to himself. After a pause he looked up at me, and said, "I suppose you can't help? I shall have to find something to do very soon."

"Have you no other friends you could ask?" I was in no position to help myself then, let alone others.

"I have a few, but they are all in the same boat. . . ."

When I left him, the full moon was high in the sky and the night was very still.

四

山陽的教育事業的狀況很不佳。我到校兩月,得不到一文薪水,只得連煙捲也節省起來。但是學校里的人們,雖是月薪十五六元的小職員,也沒有一個不是樂天知命的,仗著逐漸打熬成功的銅筋鐵骨,面黃肌瘦地從早辦公一直到夜,其間看見名位較高的人物,還得恭恭敬敬地站起,實在都是不必「衣食足而知禮節」〔8〕的人民。我每看見這情狀,不知怎的總記起連殳臨別託付我的話來。他那時生計更其不堪了,窘相時時顯露,看去似乎已沒有往時的深沉,知道我就要動身,深夜來訪,遲疑了許久,才吞吞吐吐地說道:

「不知道那邊可有法子想?——便是鈔寫,一月二三十塊錢的也可以的。我……。」

我很詫異了,還不料他竟肯這樣的遷就,一時說不出話來。

「我……,我還得活幾天……。」

「那邊去看一看,一定竭力去設法罷。」

這是我當日一口承當的答話,後來常常自己聽見,眼前也同時浮出連殳的相貌,而且吞吞吐吐地說道「我還得活幾天」。到這些時,我便設法向各處推薦一番;但有什麼效驗呢,事少人多,結果是別人給我幾句抱歉的話,我就給他幾句抱歉的信。到一學期將完的時候,那情形就更加壞了起來。那地方的幾個紳士所辦的《學理周報》上,竟開始攻擊我了,自然是決不指名的,但措辭很巧妙,使人一見就覺得我是在挑剔學潮〔10〕,連推薦連殳的事,也算是呼朋引類。

我只好一動不動,除上課之外,便關起門來躲著,有時連煙捲的煙鑽出窗隙去,也怕犯了挑剔學潮的嫌疑。連殳的事,自然更是無從說起了。這樣地一直到深冬。

下了一天雪,到夜還沒有止,屋外一切靜極,靜到要聽出靜的聲音來。我在小小的燈火光中,閉目枯坐,如見雪花片片飄墜,來增補這一望無際的雪堆;故鄉也準備過年了,人們忙得很;我自己還是一個兒童,在後園的平坦處和一夥小朋友塑雪羅漢。雪羅漢的眼睛是用兩塊小炭嵌出來的,顏色很黑,這一閃動,便變了連殳的眼睛。

「我還得活幾天!」仍是這樣的聲音。

「為什麼呢?」我無端地這樣問,立刻連自己也覺得可笑了。

這可笑的問題使我清醒,坐直了身子,點起一枝煙捲來;推窗一望,雪果然下得更大了。聽得有人叩門;不一會,一個人走進來,但是聽熟的客寓雜役的腳步。他推開我的房門,交給我一封六寸多長的信,字跡很潦草,然而一瞥便認出「魏緘」兩個字,是連殳寄來的。

這是從我離開S城以後他給我的第一封信。我知道他疏懶,本不以杳無消息為奇,但有時也頗怨他不給一點消息。待到接了這信,可又無端地覺得奇怪了,慌忙拆開來。裡面也用了一樣潦草的字體,寫著這樣的話:

「申飛……。

「我稱你什麼呢?我空著。你自己願意稱什麼,你自己添上去罷。我都可以的。

「別後共得三信,沒有復。這原因很簡單:我連買郵票的錢也沒有。

「你或者願意知道些我的消息,現在簡直告訴你罷:我失敗了。先前,我自以為是失敗者,現在知道那並不,現在才真是失敗者了。先前,還有人願意我活幾天,我自己也還想活幾天的時候,活不下去;現在,大可以無須了,然而要活下去……。

「然而就活下去么?

「願意我活幾天的,自己就活不下去。這人已被敵人誘殺了。誰殺的呢?誰也不知道。

「人生的變化多麼迅速呵!這半年來,我幾乎求乞了,實際,也可以算得已經求乞。然而我還有所為,我願意為此求乞,為此凍餒,為此寂寞,為此辛苦。但滅亡是不願意的。你看,有一個願意我活幾天的,那力量就這麼大。然而現在是沒有了,連這一個也沒有了。同時,我自己也覺得不配活下去;別人呢?也不配的。同時,我自己又覺得偏要為不願意我活下去的人們而活下去;好在願意我好好地活下去的已經沒有了,再沒有誰痛心。使這樣的人痛心,我是不願意的。然而現在是沒有了,連這一個也沒有了。快活極了,舒服極了;我已經躬行我先前所憎惡,所反對的一切,拒斥我先前所崇仰,所主張的一切了。我已經真的失敗,——然而我勝利了。

「你以為我發了瘋么?你以為我成了英雄或偉人了么?不,不的。這事情很簡單;我近來已經做了杜師長的顧問,每月的薪水就有現洋八十元了。

「申飛……。

「你將以我為什麼東西呢,你自己定就是,我都可以的。

「你大約還記得我舊時的客廳罷,我們在城中初見和將別時候的客廳。現在我還用著這客廳。這裡有新的賓客,新的饋贈,新的頌揚,新的鑽營,新的磕頭和打拱,新的打牌和猜拳,新的冷眼和噁心,新的失眠和吐血……。

「你前信說你教書很不如意。你願意也做顧問么?可以告訴我,我給你辦。其實是做門房也不妨,一樣地有新的賓客和新的饋贈,新的頌揚……。

「我這裡下大雪了。你那裡怎樣?現在已是深夜,吐了兩口血,使我清醒起來。記得你竟從秋天以來陸續給了我三封信,這是怎樣的可以驚異的事呵。我必須寄給你一點消息,你或者不至於倒抽一口冷氣罷。

「此後,我大約不再寫信的了,我這習慣是你早已知道的。何時回來呢?倘早,當能相見。——但我想,我們大概究竟不是一路的;那麼,請你忘記我罷。我從我的真心感謝你先前常替我籌劃生計。但是現在忘記我罷;我現在已經『好』了。

連殳。十二月十四日。」

這雖然並不使我「倒抽一口冷氣」,但草草一看之後,又細看了一遍,卻總有些不舒服,而同時可又夾雜些快意和高興;又想,他的生計總算已經不成問題,我的擔子也可以放下了,雖然在我這一面始終不過是無法可想。忽而又想寫一封信回答他,但又覺得沒有話說,於是這意思也立即消失了。

我的確漸漸地在忘卻他。在我的記憶中,他的面貌也不再時常出現。但得信之後不到十天,S城的學理七日報社忽然接續著郵寄他們的《學理七日報》來了。我是不大看這些東西的,不過既經寄到,也就隨手翻翻。這卻使我記起連殳來,因為裡面常有關於他的詩文,如《雪夜謁連殳先生》,《連殳顧問高齋雅集》等等;有一回,《學理閑譚》里還津津地敘述他先前所被傳為笑柄的事,稱作「逸聞」,言外大有「且夫非常之人,必能行非常之事」〔11〕的意思。

不知怎地雖然因此記起,但他的面貌卻總是逐漸模胡;然而又似乎和我日加密切起來,往往無端感到一種連自己也莫明其妙的不安和極輕微的震顫。幸而到了秋季,這《學理七日報》就不寄來了;山陽的《學理周刊》上卻又按期登起一篇長論文:《流言即事實論》。裡面還說,關於某君們的流言,已在公正士紳間盛傳了。這是專指幾個人的,有我在內;我只好極小心,照例連吸煙捲的煙也謹防飛散。小心是一種忙的苦痛,因此會百事俱廢,自然也無暇記得連殳。總之:我其實已經將他忘卻了。

但我也終於敷衍不到暑假,五月底,便離開了山陽。

IV