- 哈佛的故事:真假習明澤 [2015/04]

- 在美國如何免費看電視:ROKU好用嗎? [2013/10]

- 有史以來最蠢的哈佛學生? [2013/12]

- 華為思科的血海深仇是怎樣結下的? [2018/12]

- 付不起學費?美國上大學的省錢之道 [2013/09]

- 卡梅爾:尋找張大千在加州的足跡 [2019/01]

- 紐約哈萊姆區探秘 [2015/05]

- 在美國養個娃有多貴? [2015/01]

- 學鋼琴有用嗎? [2011/09]

- 斯坦福直線加速器SLAC探秘 [2015/09]

- 我們應該為孩子買房嗎? [2015/03]

- 選擇的負擔:我們為什麼要移民? [2014/10]

- 數學「諾貝爾獎」揭曉:又沒中國人啥事 [2014/09]

- 中國教育是世界第一嗎?從PISA考試談起 [2013/12]

- 好男人都死哪兒去啦? [2016/09]

- 家有才女 大事不好 [2011/12]

- 美國大選:投了也白投,白投也要投 [2012/10]

- 進村一周年感言:桃源夜話 [2012/06]

「科學離開了宗教就象是瘸腿的,宗教沒有科學則是瞎眼的。」(Science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind.) - 愛因斯坦。

最早聽到這句名言是很多年前。有次牧師講道時指出很多科學家是信神的,他特別舉出愛因斯坦的例子。我當時有點半信半疑,這真是愛因斯坦說的嗎?後半句比較容易理解,可前半句他為啥說「科學離開了宗教就象是瘸腿的」呢,難道不信教就不能成為好的科學家嗎?

其實搞清這個問題並不困難,只是我當時並沒有放在心上。很多年後有次在普林斯頓的拿騷大道上散步,不經意間走進了一家叫Labyrinth的書店。在樓下賣舊書的地方,尋尋覓覓,最後引起注意的是一本不起眼的小書 – 愛因斯坦的《想法和意見》(Ideas and Opinions)。這本書收集了愛因斯坦從物理學家生涯的早期到1955年去世之間的幾十篇文章,講演和書信。內容非常廣泛,從相對論,核戰爭,世界和平,人權,教育,一直到宗教和科學,林林種種。如果你想了解愛因斯坦的世界觀或者想知道他為什麼這樣受人愛戴,可以從這本書開始。

愛因斯坦以創立「相對論」而聞名於世,但他同時又是位偉大的思想家,現代的哲人。他對許多問題的思考深刻而獨到。愛因斯坦的寫作並不像暢銷書那樣可以一氣從頭看到尾,但好處是每篇都不是很長。我可以花5分鐘到20分鐘讀一篇,停下來做些別的事情。這樣也有時間回味他說了點啥。我發現這是讀此類書的最好方法。讀到36頁,赫然看見愛因斯坦有關宗教和科學的關係的四篇文章。踏破鐵鞋無覓處,得來全不非功夫。

現代人喜歡亂帖標籤,比如某某是左派,誰誰是右派;這位是信神的,那位是無神論者,等等,但現實世界要比這樣過度簡單化的分類要精微複雜的多。在完全的無神論和「聖經句句是真理」之間有很大的灰色空間,愛因斯坦就是這樣一位複雜的人。這也是為什麼宗教人士和無神論者都引用愛因斯坦來證明自己的觀點。

如果你是信神的人,好消息是愛因斯坦也相信「神」,壞消息是愛因斯坦相信的神同你相信的神並不一樣。愛因斯坦並不是傳統意義上的宗教人士,他不相信人格化的神 – 那種聽人禱告,會獎賞或懲罰人的神。他也不認為人死後有天堂。另一個角度來講,愛因斯坦又是非常屬靈的人。他在宇宙的宏大有序中看到了神的存在,並將一生的精力投入在試圖理解神的精微設計上。為此,愛因斯坦被封上好幾種標籤:不可知論者(agnostic),自然神論者(deism),泛神論者(pantheistic),等等。我覺得愛因斯坦就是愛因斯坦,沒有一個標籤是完全合適的。

當然理解愛因斯坦的最好方法不是聽任何人的二手解讀,或者淺嘗輒止於他的隻言片語,最好的方法是閱讀愛因斯坦的原著。愛因斯坦到底信神嗎?他為什麼說「科學沒有宗教就象瘸腿的」呢,以下一篇1930年11月9日發表於紐約時報雜誌題為「宗教與科學」的文章可能給出了最好的回答。

愛因斯坦在文章中闡述了宗教發展的歷史,並預言一個嶄新的宗教階段的降臨。他還試圖調和宗教與科學的矛盾。愛因斯坦成功地做到這點嗎?不得而知。他當然有不少贊同者,但有些科學家對他的沒有宗教情懷就搞不了科學的說法提出批評。我並不懷疑愛因斯坦是真正感受到他所說的「宇宙宗教情感」,這也是他科學研究的原動力。當然並不是所有科學家,尤其是現代科學家,都是像他這樣的。比如當代最偉大的物理學家,霍金,就非常著名地宣稱:創造宇宙並不需要上帝(God was not necessary to create the universe)。

宗教與科學

發表於紐約時報雜誌(New York Times Magazine)

(翻譯:白露為霜)

人類所做的和所想的一切都源於滿足切身的需求和舒解自己的痛苦。如果人們想理解屬靈運動及其發展,他必須時刻牢記這點。感受和渴望是所有人類努力和人類創造背後的動力,不管後者以何種崇高的幌子展示給我們。什麼樣的感受和需求使人產生最廣泛意義上的宗教思想和信仰呢?思考一下就足以告訴我們,非常不同的情感導致了宗教思想和經驗的誕生。讓原始人產生宗教觀念的首先是「恐懼」–害怕飢餓,猛獸,疾病,死亡。因為人在這個階段對因果關係的認識通常還不發達,人的腦子裡產生出與自身相似的虛幻的神靈來:他們的願望和行動導致了這些令人恐懼的事情。因此,人們試圖通過行動和根據一代代流傳下來的傳統進行獻祭來確保這些神靈的青睞,勸說他們對凡人好一點。在這個意義上,我把它稱為是「恐懼的宗教」(religion of fear)。這種宗教,雖然不是祭司們創造的,但在某種程度上被這個特殊階層穩定下來。他們將自己打扮成眾人和他們所害怕的神靈之間的調停人,並在此基礎上架設一個霸權。世俗領袖或統治者或特權階級,其地位依賴於其他因素,經常將世俗權力與祭司階層相結合以使後者更加穩固,或者政治統治者和祭司階層在其自我利益中尋求共同點。

社會沖動(social impulses)是宗教的結晶的另一個來源。父母親或人類社區的領袖是凡人因而難免犯錯。希望得到指引,愛護和支持的願望使人形成了神的社會或道德觀念。這是天意之神(God of Providence),他保護,處置,獎勵和懲罰。這個神,取決於信徒的視野,熱愛和珍惜部落的生命,人類的生命,甚至個體的生命。安慰悲傷和未能滿足的渴望,他保存了死者的靈魂。這是神的社會或道德的觀念。

猶太經文令人讚美地展示了從恐懼的宗教到道德的宗教之發展,這個過程一直持續到新約聖經。一切文明民族的宗教,尤其是東方人的宗教,主要是道德的宗教。從恐懼的宗教到道德的宗教的發展是人類生活的一大進步。然而,認為原始宗教是完全基於恐懼而文明民族的宗教純粹基於道德的看法是一種我們必須警惕的偏見。事實是,所有宗教都是這兩種類型的不同的混合體,其差別是:在較高水平的社會生活中道德的宗教佔主導地位。

所有這些類型的共同點是他們的上帝的觀念都是擬人(anthropomorphic character)的角色。一般情況下,只有具有特殊稟賦的個體,以及極其高尚的社團,才能上升到高於這個級別的程度。但有一個屬於所有這些宗教體驗的第三個階段,儘管它的純粹的形式很少被發現:我將它稱為宇宙宗教感情(cosmic religious feeling)。對於完全沒有這種感覺的人來說這很難闡明,特別是因為它沒有人格化的上帝的概念。

有些人感覺到人類的慾望和目標的徒勞以及自然和思想世界所透露出來的崇高和奇妙的秩序。個體的存在給他一種被囚禁的感覺,他想把宇宙作為一個顯著的整體來體驗。宇宙宗教感情的萌芽已經處在早期的發展階段,例如,在許多大衛的詩篇(Psalms of David)以及先知書(Prophets)里的一部分。佛教,我們特別從叔本華的精彩著作中了解到,包含了更加濃重的這一元素。

這種沒有教條,沒有人型的神,也沒有教堂,以及在它之上建立的中心教義的宗教的感覺是各個時代的宗教天才與眾不同的地方。因此,恰恰是在歷代的異端邪說者中我們發現了充滿了這種最高的宗教感情的人。在許多情況下,他們被同代人視為無神論者,有時也被視為為聖人。從這個角度來看,德謨克利特(Democritus),阿西西的弗朗西斯(Francis of Assisi),和斯賓諾莎(Spinoza)其實很相似。

假如它沒有明確的上帝概念,沒有神學理論,宇宙宗教感情又如何能從一個人傳遞到另一個人呢?在我看來,藝術和科學的最重要的功能就是喚醒這種感覺,並使之在那些能感受到它的人們中存活下來。

這樣,我們便得出了與通常很不相同的科學和宗教的關係的概念。當人從歷史上來看待這一關係,由於很明顯的原因,他很容易得出科學與宗教是不可調和的死敵。完全相信因果定律(law of causation)的普遍適應性的人是不可能理會神靈在事件過程中加以干涉的想法 - 當然前提是他非常嚴肅地看待因果關係的假設。他不需要恐懼的宗教,同樣也不需要社會或道德的宗教。獎勵和懲罰的神對他來說是不可想象的。原因很簡單,一個人的行為是由外部和內部的需求決定的,所以,在神的眼中,就像一個沒有生命的物體不能對它的運動負責一樣,人也不能為他的行為更多地負責。科學也因此被指控破壞了道德,但這個指責是不公平的。一個人的道德行為,應基於同情,教育,以及社會關係與需求。宗教的基礎不應是前提。人如果靠著對懲罰的恐懼和對死後的獎賞的希望來約束那實在是太差勁了。

所以很容易看出為什麼教會一直在同科學鬥爭並迫害獻身科學的人。另一方面,我認為宇宙宗教感情是科學研究最有力最高尚的動機。只有那些付出了巨大的努力和奉獻,沒有它理論科學的先驅工作無法實現的人,才能夠把握這種情感的強度。唯有這樣的工作,雖然同直接的現實生活很遙遠,才能產生這種情感。這是對宇宙的合理性多麼堅定的信念和對了解[真理]多麼強烈的渴望,它難道不是心靈的微弱反映透露在這個世界上嗎,正是它使得開普勒和牛頓能經過多年孤獨的勞動解開的天體力學的原則!那些對科學研究的了解主要來自其實用的結果對人的心態很容易得出完全虛假的印象,被持懷疑態度的世界所包圍,通向志趣相投的道路散落在廣闊的世界和不同的世紀。只有那些為了相似的目的獻出了自己的生命的人能有一個生動的理解是什麼激發了這些人,儘管有無數次的失敗,給予他們力量使之忠於自己的理想。是宇宙宗教感情給人這樣的力量。一位同代人曾經說過,我以為沒有不妥,在我們這個物慾橫流的時代,嚴肅的科學工作者是唯一的深刻的宗教人士(profoundly religious people)。

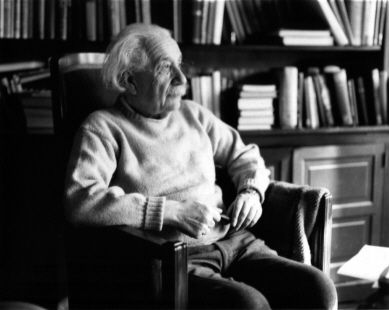

愛因斯坦在普林斯頓

Religion and Science

Albert Einstein

The following article by Albert Einstein appeared in the New York Times Magazine on November 9, 1930 pp 1-4. It has been reprinted in Ideas and Opinions, Crown Publishers, Inc. 1954

Everything that the human race has done and thought is concerned with the satisfaction of deeply felt needs and the assuagement of pain. One has to keep this constantly in mind if one wishes to understand spiritual movements and their development. Feeling and longing are the motive force behind all human endeavor and human creation, in however exalted a guise the latter may present themselves to us. Now what are the feelings and needs that have led men to religious thought and belief in the widest sense of the words? A little consideration will suffice to show us that the most varying emotions preside over the birth of religious thought and experience. With primitive man it is above all fear that evokes religious notions - fear of hunger, wild beasts, sickness, death. Since at this stage of existence understanding of causal connections is usually poorly developed, the human mind creates illusory beings more or less analogous to itself on whose wills and actions these fearful happenings depend. Thus one tries to secure the favor of these beings by carrying out actions and offering sacrifices which, according to the tradition handed down from generation to generation, propitiate them or make them well disposed toward a mortal. In this sense I am speaking of a religion of fear. This, though not created, is in an important degree stabilized by the formation of a special priestly caste which sets itself up as a mediator between the people and the beings they fear, and erects a hegemony on this basis. In many cases a leader or ruler or a privileged class whose position rests on other factors combines priestly functions with its secular authority in order to make the latter more secure; or the political rulers and the priestly caste make common cause in their own interests.

The social impulses are another source of the crystallization of religion. Fathers and mothers and the leaders of larger human communities are mortal and fallible. The desire for guidance, love, and support prompts men to form the social or moral conception of God. This is the God of Providence, who protects, disposes, rewards, and punishes; the God who, according to the limits of the believer's outlook, loves and cherishes the life of the tribe or of the human race, or even or life itself; the comforter in sorrow and unsatisfied longing; he who preserves the souls of the dead. This is the social or moral conception of God.

The Jewish scriptures admirably illustrate the development from the religion of fear to moral religion, a development continued in the New Testament. The religions of all civilized peoples, especially the peoples of the Orient, are primarily moral religions. The development from a religion of fear to moral religion is a great step in peoples' lives. And yet, that primitive religions are based entirely on fear and the religions of civilized peoples purely on morality is a prejudice against which we must be on our guard. The truth is that all religions are a varying blend of both types, with this differentiation: that on the higher levels of social life the religion of morality predominates.

Common to all these types is the anthropomorphic character of their conception of God. In general, only individuals of exceptional endowments, and exceptionally high-minded communities, rise to any considerable extent above this level. But there is a third stage of religious experience which belongs to all of them, even though it is rarely found in a pure form: I shall call it cosmic religious feeling. It is very difficult to elucidate this feeling to anyone who is entirely without it, especially as there is no anthropomorphic conception of God corresponding to it.

The individual feels the futility of human desires and aims and the sublimity and marvelous order which reveal themselves both in nature and in the world of thought. Individual existence impresses him as a sort of prison and he wants to experience the universe as a single significant whole. The beginnings of cosmic religious feeling already appear at an early stage of development, e.g., in many of the Psalms of David and in some of the Prophets. Buddhism, as we have learned especially from the wonderful writings of Schopenhauer, contains a much stronger element of this.

The religious geniuses of all ages have been distinguished by this kind of religious feeling, which knows no dogma and no God conceived in man's image; so that there can be no church whose central teachings are based on it. Hence it is precisely among the heretics of every age that we find men who were filled with this highest kind of religious feeling and were in many cases regarded by their contemporaries as atheists, sometimes also as saints. Looked at in this light, men like Democritus, Francis of Assisi, and Spinoza are closely akin to one another.

How can cosmic religious feeling be communicated from one person to another, if it can give rise to no definite notion of a God and no theology? In my view, it is the most important function of art and science to awaken this feeling and keep it alive in those who are receptive to it.

We thus arrive at a conception of the relation of science to religion very different from the usual one. When one views the matter historically, one is inclined to look upon science and religion as irreconcilable antagonists, and for a very obvious reason. The man who is thoroughly convinced of the universal operation of the law of causation cannot for a moment entertain the idea of a being who interferes in the course of events - provided, of course, that he takes the hypothesis of causality really seriously. He has no use for the religion of fear and equally little for social or moral religion. A God who rewards and punishes is inconceivable to him for the simple reason that a man's actions are determined by necessity, external and internal, so that in God's eyes he cannot be responsible, any more than an inanimate object is responsible for the motions it undergoes. Science has therefore been charged with undermining morality, but the charge is unjust. A man's ethical behavior should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties and needs; no religious basis is necessary. Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hopes of reward after death.

It is therefore easy to see why the churches have always fought science and persecuted its devotees. On the other hand, I maintain that the cosmic religious feeling is the strongest and noblest motive for scientific research. Only those who realize the immense efforts and, above all, the devotion without which pioneer work in theoretical science cannot be achieved are able to grasp the strength of the emotion out of which alone such work, remote as it is from the immediate realities of life, can issue. What a deep conviction of the rationality of the universe and what a yearning to understand, were it but a feeble reflection of the mind revealed in this world, Kepler and Newton must have had to enable them to spend years of solitary labor in disentangling the principles of celestial mechanics! Those whose acquaintance with scientific research is derived chiefly from its practical results easily develop a completely false notion of the mentality of the men who, surrounded by a skeptical world, have shown the way to kindred spirits scattered wide through the world and through the centuries. Only one who has devoted his life to similar ends can have a vivid realization of what has inspired these men and given them the strength to remain true to their purpose in spite of countless failures. It is cosmic religious feeling that gives a man such strength. A contemporary has said, not unjustly, that in this materialistic age of ours the serious scientific workers are the only profoundly religious people.

愛因斯坦宗教和科學方面的相關閱讀:

http://einsteinandreligion.com/

- [06/30]與恐龍同行的孩子們

- [07/07]前白宮秘書長盧沛寧談留給孩子的產業

- [07/25]先有雞還是先有蛋:當然是先有蛋!

- [07/31]哈佛不需要SAT 科目考試了:你該怎麼辦?

- [08/17] 愛因斯坦相信神嗎?

- [08/24]湖依舊,人已老:時間都去哪兒了?

- [09/02]返樸歸真:帶你逛逛美國的菜市場

- [09/07]數學「諾貝爾獎」揭曉:又沒中國人啥事

- [09/19]與天斗、與地斗、與小三斗?

- [09/29]寬客人生:是誰搞垮華爾街的?

- [10/06]選擇的負擔:我們為什麼要移民?

- [11/11]美國大學升學作文題賞析:芝加哥大學

- 查看:[白露為霜的.最新博文]

- 查看:[大家的.最新博文]

- 查看:[大家的.留學生活]

發表評論 評論 (58 個評論)

- 回復 fanlaifuqu

- 謝謝白露。

- 回復 ChineseInvest88

- 有點深哈。

fanlaifuqu: 謝謝白露。

- 回復 越湖

- 最後一段說得非常好。

「Only one who has devoted his life to similar ends can have a vivid realization of what has inspired these men and given them the strength to remain true to their purpose in spite of countless failures. It is cosmic religious feeling that gives a man such strength. A contemporary has said, not unjustly, that in this materialistic age of ours the serious scientific workers are the only profoundly religious people.「

引用您的翻譯:

「只有那些為了相似的目的獻出了自己的生命的人能有一個生動的理解是什麼激發了這些人,儘管有無數次的失敗,給予他們力量使之忠於自己的理想。是宇宙宗教感情給人這樣的力量。一位同代人曾經說過,我以為沒有不妥,在我們這個物慾橫流的時代,嚴肅的科學工作者是唯一的深刻的宗教人士「

- 回復 fanlaifuqu

- 自詡無神論者,與生長在共黨的環境里太久有點關係,但不全是。但自明相對的卑微,低下與無知,不敢全然否定神的存在。

- 回復 白露為霜

- 謝謝留言。愛因斯坦的感受相當獨特,也許不是所有科學家都會同意。

越湖: 最後一段說得非常好。

「Only one who has devoted his life to similar ends can have a vivid realization of what has inspired these men and given them th

- 回復 白露為霜

- 那就是介於無神論者和不可知論者之間。

fanlaifuqu: 自詡無神論者,與生長在共黨的環境里太久有點關係,但不全是。但自明相對的卑微,低下與無知,不敢全然否定神的存在。

帽子橫飛哈~

- 回復 白露為霜

- 一般人這樣認為也不奇怪。但科學理解的範圍越來越大,宗教只能退縮人類未知的邊緣,這樣的日子是很難過的。

前兆: 當代科學解釋不了的,只能推給「神」。所以,「科學離開了宗教就象是瘸腿的,......」,「上帝等於我不知」,......

- 回復 白露為霜

- 儒家也許不能稱為完整的宗教。佛教,印度教有宇宙神的概念,但也有人格化神在裡面,信徒到廟裡拜菩薩或其他神,求福等。

徐福男兒: 在人格神與宇宙中神的精微存在兩者之間,佛教與中國的儒家的認知都屬於後者。道家也屬於後者,到了道教才發展出前者的認知來,那明顯是為了忽悠農夫炊婦的了。

- 卿心依舊溫柔:【飛騨の里民俗村之舊中籔家】

- qwxqwsean:留學生的伙食

- 心路獨舞:那一場花事

- LaoQian:老錢: 窩裡斗的源由/「長不大」的中文學校

- 白露為霜:哈佛不需要SAT 科目考試了:你該怎麼辦?

- 白露為霜:先有雞還是先有蛋:當然是先有蛋!

- 金竹陶器:怎麼碰不到女流氓

- 金竹陶器:一葉障目博士

- 金竹陶器:斯坦福女廁驚魂記

- 白露為霜:前白宮秘書長盧沛寧談留給孩子的產業

- 白露為霜:與恐龍同行的孩子們

- 白露為霜:小寶的畢業論文

- 白露為霜:普林斯頓團聚日必做的八件事

- 心路獨舞:夜有微瀾

- nn1111:出國后的我們(ZT)

- 奧之細道:「其出東門,有女如雲」---晒晒我的大學

- 白露為霜:血流成河:從數字看今年伯克利新生錄取